Water Torture: Nikon D850 vs Sony A7RIII, Canon 5D Mk IV & Olympus E-M1 II

posted Saturday, January 6, 2018 at 2:12 PM EDT

As we describe in the article announcing our overall winner for the best camera of 2017, it was a difficult choice between the Nikon D850 and Sony A7R III. Both are exceptionally strong cameras, with features that will appeal to different groups of photographers. Given how tough the decision was, we felt that general ruggedness and particularly weather resistance could be an important differentiator between the two. So, after asking and receiving permission from both manufacturers to subject the cameras to a "weather" test, we set out to do just that.

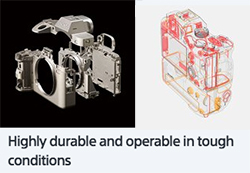

“Weather resistance” stands out as the one area of high-end camera performance where there’s no industry-wide standard that defines what it means. Cameras claiming “weather resistance” range from ones with comprehensive arrays of seals and gaskets to others that just rely on quasi-tight fits between parts and the hope that no water or dust happens to approach in the wrong direction.

In the past, Sony has described many of their models as "weather resistant", but a teardown of the A7SII by Roger Cicala at LensRentals.com showed only one gasket in the camera, a partial one around the battery compartment. As Roger said at the time, it might be that Sony felt the camera's parts fit tightly enough that they didn't need gaskets, but other manufacturers have always made a big deal to us about the number and placement of gaskets on their weather-resistant bodies. Sony's manufacturing process may well be able to maintain tighter tolerances between parts, such that gaskets were unnecessary, but it seemed at odds with the rest of the industry.

The situation changed somewhat with the A9 and the most recent A7R III, with Sony calling attention to physical seals at a number of points on both bodies. A recent teardown of the A7R III showed more seals and gaskets than we'd seen previously, but didn't go deep enough to show whether or not there were seals around many top-panel controls. Some Sony lenses sport visible seals at the flange mount, to prevent water from entering the camera body by that route, so at least that critical interface is protected when shooting with those lenses.

Nikon’s high-end full-frame camera bodies have had a well-deserved reputation for ruggedness and general weather resistance (whatever that means) for a long time now, so we wondered how Sony’s recent improvements in that area would measure up.

Given that there isn’t any accepted standard for weather resistance, though, we felt it important to see how some other pro-level camera bodies would respond to the same conditions. There may not be a standard, and our tests may not perfectly simulate a natural rainstorm (see below), but we could at least see how different models performed when confronted with the same conditions. Accordingly, we tested not just the D850 and A7R III, but included the Canon EOS 5D Mark IV and Olympus OM-D EM-1 as well, two pro-category winners from our 2016 COTY awards. All four cameras received as close to the same treatment as we could manage, and the results were ... illuminating.

for proper weather sealing. Two mirrorless models (A7R III and E-M1 II)

and two DSLR's (5D Mark IV and D850)

How we tested

We should say up front that, clearly, none of these cameras are “waterproof” in any accepted sense of the word. None of them are designed to be submerged, so there’s certainly some level of water exposure at which all of them will fail. Our intent wasn’t to test to failure, but rather to provide a reasonable simulation of challenging but realistic conditions a user might encounter in the field.

We spent a good bit of time researching things like natural raindrop sizes, acceleration rates and terminal velocities, before realizing that the best we could hope for in any near term was to just approximate a reasonable rate of overall precipitation. The issue was that easily-accessible water sources (garden-hose sprayers) tended to produce more droplets of smaller size for a given overall precipitation rate than would be typical of natural rainfall. Larger drops from natural rain have a higher terminal velocity, so will strike with more force, but there'll be fewer of them for a given overall precipitation rate than any “rainfall” we could easily simulate. So we had more, smaller drops, striking the cameras more gently than the same amount of natural rain.

What we aimed for were two different scenarios, one intended to mimic a strong but not torrential rainstorm (a very rough estimate would be 0.2-0.4 inches per hour), the other a much lighter precipitation, basically a very heavy mist, as you might encounter at the base of a waterfall, or the streets of London for that matter.

The “rainstorm” scenario was mimicked by a garden-hose nozzle with a roughly cone-shaped spray, aimed upward so the droplets would fall freely from a height of 4-5 feet (1.2 - 1.5 meters) onto the cameras. Falling from that height, the droplets (~~1-2mm?) wouldn’t be at their terminal velocity, but as noted, there would be more of them striking the cameras per unit of time than would be the case in a rainstorm of similar intensity. (Note that the hose spray was not aimed directly at the cameras. The spray arced up and over at a maximum height of 4-5 feet above the cameras, and the droplets fell freely from that height - so the velocity with which they hit the cameras was somewhat lower than would be the case in natural rainfall.)

The “mist” scenario was intended to be much more gentle on the cameras, in that there would be less water overall, and also arriving with much less force: The mist more or less just drifted over the cameras, such that we had to redirect the hose nozzle in response to even slight breezes.

The cameras all got 15 minutes of “rainstorm” and 15 minutes of “mist”; we checked them carefully after each round. We were careful to thoroughly dry the exteriors of the cameras before opening them, to make sure that any water we might find inside didn’t inadvertently get there from the outside, as we handled the cameras and opened them.

Despite this caution, all of the cameras except the Canon 5D Mark IV tended to collect a thin bead of water externally, right around the flange mount, between the lens and the flange itself. It was almost impossible to remove this with the towel we were using, as the gaps involved were very small, and surface tension caused the water to wick into the tiny cracks. We tried to remove the lenses by pulling them straight away from the camera bodies, so as to not smear these little beads of water across the surface of the flange, which could make it appear that the lens/camera seal wasn't watertight. Despite seeing small amounts of water on the surfaces of the flanges, we don't think any of the cameras in the test leaked any water into the camera through this route, and don't view the lens/camera seal to be an issue for any of the bodies and lenses tested.

Video of the results!

Here's a brief video, to give you a clearer flavor of what we did:

The sequence of tests

We started out testing just the Nikon D850 and Sony A7RIII, first subjecting them to a "rainstorm" test, and later following up with a "mist" test, thinking it might be a bit more forgiving, and a less severe challenge. (It turned out that wasn't the case, see the results below.) The Sony took in a significant amount of water to the battery compartment, while the Nikon did just fine save for a minor issue that was easily addressed. At that point, we decided that we should really include a couple of other top-tier cameras, to know whether the Sony or Nikon was more representative of this grade of cameras generally. So we added a Canon 5D Mark IV and Olympus E-M1 Mark II to the test, and ran the D850 through again, this time with a more protective rubbery hot shoe cover (the optional BS-3 cover). All the cameras received pretty identical treatment, the main differences being that the Nikon D850 ended up going through two sets of water-torture tests, while the others only saw one. (Given the initial results, we had no fear that the D850 wouldn't survive a second round, and felt it important to collect some results with the BS-3 hot shoe cover.)

The results

Given that the A7R III has a significant number of environmental seals (see the screen capture to the right, taken from the Sony website), we were surprised that it had as hard a time with our test as it did - particularly given that all of the other cameras passed it easily.

As you can see in the video above, after the first "rainstorm" test, the D850 ended up with a large drop of water inside the viewfinder eyepiece, but it didn't interfere with camera operation in any way, and was easily removed by dabbing it with a towel, after removing the eyepiece optic.

In contrast, the A7R III had a lot of water in its battery compartment. This must have entered through the top panel somehow, as it was up inside the battery compartment, vs just in the bottom, and the bottom of the camera wasn't actually touching the table surface: It was mounted on a 70-200mm lens, and the whole assembly was resting on the tripod mount of the lens throughout the test.

the A7R III took a noticeable amount of water into the battery compartment.

At this point, while it got pretty wet, the A7R III was still working just fine; it focused and shot perfectly well, and didn't show any ill effects whatever from its dousing. We set it aside with its sensor compartment, battery compartment and card compartment all open, to help air-out any remaining moisture. After thinking about this result for a bit, we wondered if perhaps our initial test was too harsh. The overall amount of water involved was only representative of a moderately heavy rainstorm, but still... Maybe we should try something a bit less challenging?

With this thought in mind, we decided to try a "mist test" the next day. Lots less water, much more gentle and smaller droplets, etc. We'd also try the BS-3 hot shoe cover on the Nikon to see how it performed, even though the "rainfall" would be a lot lighter.

Unfortunately, this second test proved to be the A7R III's undoing :-/ It was working fine beforehand and seemed to survive the experience OK, but then...

As soon as we were done dousing, we carried the D850 and 5DIV inside, then went back out to retrieve the Sony and the Olympus. As soon as we stepped outside, though, we heard a rapid clicking noise coming from the direction of the table holding the cameras. Huh?... It turned out the sound was coming from the A7R III, which was firing continuously. It was set to continuous-high mode, but its power switch was turned off. The only way we could get it to stop chattering away was to drop the battery. When we did, there was no sign of any water in the battery compartment, but watching the shutter actuate, we could see that there was water on the shutter blades themselves. Dropping the battery at the right moment let us catch it with the shutter closed, so we could (very carefully) dab at it with a tissue, to remove most of the water.

Hoping we hadn't done any permanent damage, we set the A7R III under a fluorescent lamp, providing very gentle warmth in the dry air of our office. (The camera body ended up at perhaps 80-90 degrees F, and the air in the office was quite dry, thanks to a cold wave that hit Atlanta just after our tests.) After a day of gentle drying, we were dismayed to find the A7R III completely unresponsive. With a freshly-charged battery, it didn't respond at all when we toggled the power switch on and off. Our hearts heavy, we left it for some more drying, hoping it would recover.

Fortunately, by the following day, the A7R III had returned to full health! It now shoots and focuses just fine, and gives no sign of any lingering problems from its water exposure. So while it had some significant issues as the result of our test, it seems to have recovered 100%. This is good news for anyone who might unexpectedly get caught in a rainstorm with their A7R III; just open its compartments and let it air out for a while, and there's a good chance it'll be none the worse for wear.

(Do note, though, that this would be the case with rainwater, which is effectively distilled water and so leaves no residue behind. We were a little concerned because our test used tap water, which has minerals in it. Salt water or salt spray would be an entirely different proposition; check this article by Roger Cicala on what happens to a camera when it's exposed to salt water.)

As to the other cameras (the Canon 5D Mark IV and Olympus E-M1 Mark II), neither one showed any effect from our water challenge. We found no water in any of their compartments or viewfinders, and neither had any operational difficulties whatsoever. We'd expected this based on our own previous experiences with each camera, but it was a comforting reassurance.

We don't know to what extent it was responsible for the leaks, but one thing we noticed about the A7R III was that its flat top panel tended to accumulate "puddles" of water during the test, on both sides of the chassis, and on the right side, pooling near the EV-adjust dial. As noted below, this might be less of an issue for handheld shooting, where the camera would rarely be held dead-level, but the more angled surfaces of the other cameras prevented this from happening at all. Perhaps this could be a direction for Sony designers to explore in future design iterations?

Ways in which this wasn’t a “real world” test

Having discussed the results, we think it's important to note again that this wasn't a scientifically-controlled, statistically-accurate representation of either a real rainstorm or the waterfall-mist scenario. As noted, while we tried to reproduce typical if challenging conditions, there were a number of ways in which this wasn’t a good simulation of natural shooting conditions. The important thing is that the cameras all received essentially the same treatment, to the extent that we could provide it. Still, the following points should be noted:

-

In the real world, raindrops would be larger and arrive less frequently, but with more force.

-

In the real world, hand-held cameras wouldn’t accumulate as much water on their top decks, because they wouldn’t always be held level, as they were while sitting on the mesh tabletop we had them on. (Our test conditions might simulate a wildlife photographer shooting with a long tele on a tripod, though.) Water sitting on the cameras' top panels might be more challenging than droplets hitting them with some velocity.

-

In the real world, most photographers would probably make at least some effort to protect their cameras from the elements. (It’s common to see various sorts of rain shields in use by pro sports shooters, standing along the sidelines at major sports events.) So our test conditions probably represented somewhat of a worst case.

-

BUT… In the real world, rain- or mist-storms usually last more than 15 minutes each. So while our "rainstorm" was a moderately heavy one, it was also quite short-lived. We don't know what would happen to any of the cameras we tested if they were exposed to rainy weather across an entire day of shooting. This is just one, limited data point...

-

These were deliberately challenging conditions. You’d have to be a little hard-core to stand out in these kinds of conditions (although 15 minutes at a stretch might be endurable even for the less gung-ho). Some of us at IR fit the hard-core profile (check out Dave Pardue’s story of shooting with the Fujifilm X-T2 in the teeth of an approaching hurricane), while others of us aren’t nearly that, ...uh… “committed” :-)

Conclusion

Truthfully, we were sad to see the A7R III have such a hard time in this test. It's a fantastic camera, absolutely at the cutting edge of what's possible with photographic technology today. Even after this test, those of us at IR who were fans previously would still happily buy one, because we almost never photograph in conditions approaching those in the test. But as we said in our 2017 Camera of the Year announcement article, Sony needs to up their environmental-sealing game if they want to compete in this high-end/professional market segment. We'd feel differently if all the cameras failed the test; we would have concluded that the test was just too harsh for the current state of the market, even though it was a reasonable representation of conditions a camera might be exposed to. That wasn't the case, though; the D850 had a very minor problem with leakage into its viewfinder, that seems to be entirely solved by using the BS-3 hot shoe cover - and the 5DIV and E-M1II had no problems whatsoever.

(Nikon D850; Olympus E-M1 Mark II; Canon 5D Mark IV)

One thing that is clear is that the camera industry needs some sort of standard for levels of weather resistance. There's clearly a wide range of performance in this area, and without a definition, "weather resistant" is a meaningless term. To quote The Cynic's Photography Dictionary, "Weather resistant - A term that consumers falsely define as 'weather proof' and camera companies accurately define as 'the warranty doesn't cover water damage.'"

Here's hoping the industry can come up with a meaningful standard for weather resistance; in the meantime, please share your thoughts on the subject (politely) in the comments below, and be sure to check out our 2017 Camera of the Year Awards!

[Editor's note: We didn't have a Panasonic GH5, Pentax K1 nor a Fujifilm X-T2 sample on hand the week we performed these tests, or we would have gladly included them.]

the A7R III took a noticeable amount of water into the battery compartment.

Sony A7R Mark III vs Nikon D850

Olympus E-M1 Mark II and the Canon 5D Mark IV. We included the A7R III in this shot as an illustration, but didn't expose it to the full rainstorm test again, not wanting to damage it.