The obsessive eye of Eugène Atget: Master photographer’s images of “Old Paris” still resonate

posted Friday, January 18, 2013 at 1:17 PM EST

"He was… a photographer of such authority and originality that his work remains a benchmark against which much of the most sophisticated contemporary photography measures itself. The pictures that he made… are seductively and deceptively simple, wholly poised, reticent, dense with experience, mysterious, and pure."

-- "Looking at Photographs" by John Szarkowski

In the end, Eugène Atget appeared to be a tragic figure, who roamed the streets of Paris in a long overcoat that was as frayed and worn as his life had become. However, this image, as captured by the American photographer Berenice Abbott, obscures the reality of a photographer of immense talent whose life is a story of obsession and steel-willed pursuit of images. With even the most cursory glance at any of his tens of thousands of images, Atget's vision is startlingly modern and breathtaking in its depth. From decisive moments to surreal architectural studies, it is an astonishing life's work.

I was introduced to Agtet's photography by a friend, the photographer Scotty Sapiro, who had worked in Paris as an assistant to the American photographer and Dadaist painter Man Ray. In the 1920s, Ray's studio was just a few doors away from Atget's apartment. They met one day and Atget showed Ray his photos. Ray was amazed by what he called their "surreal impulse" -- a mixture of the real and the dreamlike, it seemed the very definition of surrealism. And he bought 50 prints on the spot.

Sapiro said that, over time, "Man had recognized Atget's talent but it took him awhile before he realized the expanse of the guy's work."

Finding his life's passion

Born in Bordeaux in 1857, Eugène Atget was raised by his grandparents after his parents died when he was just 6 years old. In the 1870s, as a teenager, he was a cabin boy on large steamers, but quickly fell out of love with the sea and turned his sights to the stage. He found little work, and by 1887 his theater career was over. He thought of becoming a painter, but realized he had little talent in that direction either.

Then in 1888, he taught himself photography and began to take portraits photos in the Somme region of Northern France. Two years later, he went to Paris looking for work. Once he found a small studio space, he proudly put a sign on his door announcing "Documents for Artists."

"What move those of genius, what inspires their work is not new ideas, but their obsession with the idea that what has already been said is still not enough."

-- Eugène Delacroix, painter.

Eugène Atget was arguably the world's first commercial stock photographer. He went to his clients to sell them photographs, instead of selling pictures in a studio. For the next 30 years, he developed a client base that included painters, illustrators, engravers, sculptors and set designers. He took thousands of images of Paris with his large and rather awkward view camera. What's ironic is that these gorgeous photographs were not used themselves but instead served as "references" for other visual purposes.

Possessing all of Old Paris

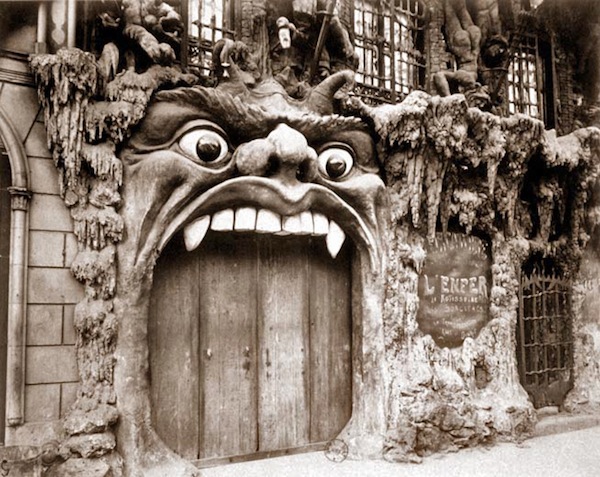

For Atget, 1898 proved to be a decisive year. The City of Paris embarked on huge public works projects, including construction of the Métro -- an underground subway -- raising concern among historians and others that the old Belle Époque Paris would be lost forever. Atget set out to document the old city before its destruction came at the hands of the modernizers. Embarking each day with his camera, he photographed the doomed streets and soon to be demolished buildings. And now he had a new clientele made up of the city's historians, amateur scholars and archival institutions, as well as hopes for more income.

Throughout his life -- working mainly in obscurity -- Atget never earned much money and he lived incredibly frugally. He would reuse pieces of paper until there was no room to write on them, and his lunch was often just some warm milk and a baguette. Yet, Atget persisted with his craft -- buying glass-plates, processing chemicals and print paper before food.

In 1920, Atget offered the French government a large number of his glass-plate negatives. Prior to this, he had always sold prints. But now at the age of 63, he wanted to find a secure place for his images to be preserved.

Writing to the minister of fine arts he said, "For more than 20 years I have been working alone and of my own initiative in all the old streets of Old Paris to make a collection of 18x24 centimeter photographic negatives: artistic documents of beautiful urban architecture from the 16th to the 19th centuries… Today this enormous artistic and documentary collection is finished; I can say I possess all of Old Paris."

The minister responded by purchasing more than 2,600 of Atget's negatives for just 10,000 francs.

A burst of life before the end

The sale improved Atget's financial condition a little, but did more in reassuring him about his creative vision. In the last years of his life, he revisited many of the places he had photographed, re-photographing them with a new confidence and a more personal, poetic sensibility. In his photos of the Parc de Sceaux, south of Paris, he turned the park's statues into living ghosts of the past that were in some ways a metaphor for his life's work.

This burst of creativity was short lived. In the summer of 1926, his companion of 30 years, the actress Valentine Campagon, died. Alone and disconsolate, he was photographed in 1927 by the photographer, Berenice Abbott, then Man Ray's assistant. She made her iconic portrait of a shrunken old man in an oversized overcoat. Later that year Eugène Atget was dead. But luckily for us, his indelible images continue to breathe with life and stoke passions of the photographers who followed in his footsteps.