Not-so-secret atomic tests: Why the photographic film industry knew what the American public didn’t

posted Tuesday, February 26, 2013 at 6:07 PM EDT

It's one of the dark marks of the U.S. Government in the 20th century — a complete willingness to expose unwitting citizens to dangerous substances in the name of scientific advancement. It happened with the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, with the MKUltra mind control project and with the atomic bomb testing of the 1940s and 50s. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) knew that dangerous levels of fallout were being pumped into the atmosphere, but didn't bother to tell anyone. Well, anyone except the photographic film industry, that is.

Photographic film is particularly radiosensitive -- that's the reason why you see dosimeters made from the stuff, as they can be used to detect gamma, X-ray and beta particles. But in 1946, Kodak customers started complaining about film they had bought coming out fogged.

Fogged Kodak film.

Photo courtesy of Oak Ridge Associated Universities

Eastman Kodak investigated, and found something mighty peculiar: the corn husks from Indiana they were using as packing materials were contaminated with the radioactive isotope iodine-131 (I-131). Eastman Kodak at the time had some of the best researchers in the country on its team (the company even had its own nuclear reactor in the 1970s), and they discovered something that was not public knowledge: those farms in Indiana had been exposed to fallout from the 1945 Trinity Test in New Mexico -- the world's first atmospheric nuclear bomb explosions which ushered in the atomic age. Kodak kept this exposure silent.

Some of the facts in the story are -- like the film in question -- a little hazy. Some claim Kodak's discovery happened in 1946, some in 1945. The Trinity Test was officially July of 1945, but I can believe that by the time corn was exposed to the radiation, picked, the husks converted to packing material and the film packaged and sold, it could well have been 1946. Given that the government initially denied that the Trinity Test was even nuclear, instead calling it an "ammunition explosion," perhaps Kodak's silence is more understandable.

The Trinity explosion, 16 milliseconds after detonation.

But the story doesn't end in 1946, with Kodak keeping a lid on atmospheric nuclear bomb testing by the government. The U.S. continued with atmospheric detonation tests, most famously in the Pacific, but also back on American soil in the 1950s at the Nevada National Security Site. The first test in Nevada was in January of 1951, and days later, as snow blanketed the city of Rochester, N.Y., Kodak detected spiked radiation levels that measured 25 times the norm some 1,600 miles away from the test site.

Kodak's response was twofold. It registered a complaint with the National Association of Photographic Manufacturers (NAPM), who contacted the Atomic Energy Commission, and Kodak contacted the AEC directly. According to the NAPM memo, Kodak measured 10,000 counts per minute of radiation, compared to recent unaffected snowfalls that registered only 400. The AEC released a statement to the AP claiming it was "investigating reports that snow that fell in Rochester was measurably radioactive. The reports... indicate that there is no possibility of harm to humans or animals.... All necessary precautions, including radiation surveys and patrolling, are being undertaken to insure that safety conditions are maintained."

Kodak's contacting of the AEC essentially lead to the company being brushed off by the commission, so Eastman Kodak did what any company would do: it threatened to sue. And that's when things got really weird. The AEC capitulated, and agreed to give not just Kodak, but also the entire film industry, information about nuclear tests, weather patterns, predicted fallout and more. This was information that no one else was getting, certainly not the general public.

To quote current Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) from a Senate hearing held on the subject in 1998:

"Kodak complained to the Atomic Energy Commission and that Government agency agreed to give Kodak advanced information on future tests, including 'expected distribution of radioactive material in order to anticipate local contamination.'

"In fact, the Government warned the entire photographic industry and provided maps and forecasts of potential contamination. Where, I ask, were the maps for dairy farmers? Where were the warnings to parents of children in these areas? So here we are, Mr. Chairman. The Government protected rolls of film, but not the lives of our kids. There is something wrong with this picture."

Senator Harkin's remarks about dairy farms and children reveals the dark side of this story. It's not enough that the AEC was knowingly releasing fallout into American skies, but that one of the side effects they were aware of was that it could enter the food supply, and potentially cause long term health problems. The I-131 would fall on the ground, be eaten by cattle through radioactive feed, and through their milk, be passed on to the public. Your thyroid needs iodine to function, so it builds up stores of iodine from the environment, and high concentrations of I-131 are directly linked to higher risks of radiogenic thyroid cancer -- especially from exposure during childhood. And that's exactly what happened to thousands of American children.

It turns out there's a relatively easy way to prevent thyroid cancer after exposure to I-131 -- standard iodine supplements will do. But if you're unaware of the fallout, you wouldn't know to take the countermeasure. The atmospheric tests have been linked to up to 75,000 cases of thyroid cancer in the U.S. alone. To this day, the National Cancer Institute runs a program to help people identify if they were exposed, and between 1951 and 1962, it was an awful lot of people.

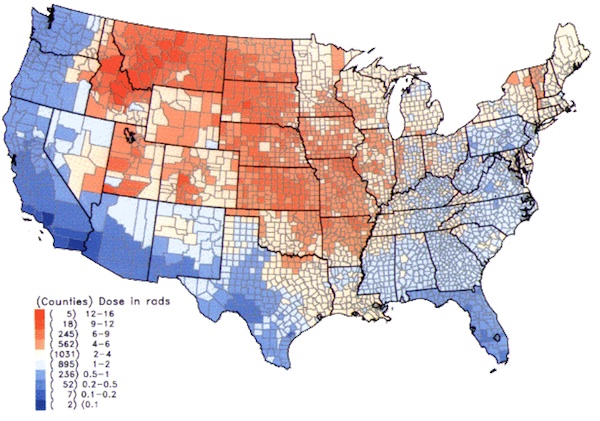

U.S. atomic testing fallout exposure map (1951-1962)

According to a report by the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IEER), there was research to indicate the danger of I-131 affecting the populace via the "milk pathway" as early as 1953, and there was fairly strong evidence by 1955. Yet the tests continued with no warnings issued to farmers or the public until the early 60s, while film manufacturers were provided with "maps and forecasts of potential contamination, as well as expected fallout distributions which enabled them to purchase uncontaminated materials and take other protective measures."

This report even claims that the AEC knew the milk had high levels of radiation, but refused to divert it away from human consumption, arguing that doing so would lead to malnutrition.

It's a bizarre and dark chapter in the history of the United States; one where the government knowingly and wittingly exposed its people to dangerous levels of radiation and fallout. And rather than warn the populace where they thought it would fall, the only outside entities who knew were those making film. After all, you wouldn't want your holiday snaps to turn out all cloudy, would you?

[Ed. note: This piece ranges far from our normal digital photography fare, but we found it an interesting historical note on a moment in time when the photo industry, military development and public health all intersected, and on how an earlier era viewed citizens' rights and safety.]

More historical photography articles you may be interested in:

Flea market mystery: 70 year old World War II slides lead to a name. Help us find him!

On Ice: 100-year-old negatives discovered in Antarctic

Famed explorer Ranulph Fiennes teams up with Cambridge to save Antarctic photos

-more-