Syria: teenage stringer pays the ultimate price for Reuters coverage

posted Monday, January 13, 2014 at 5:45 PM EDT

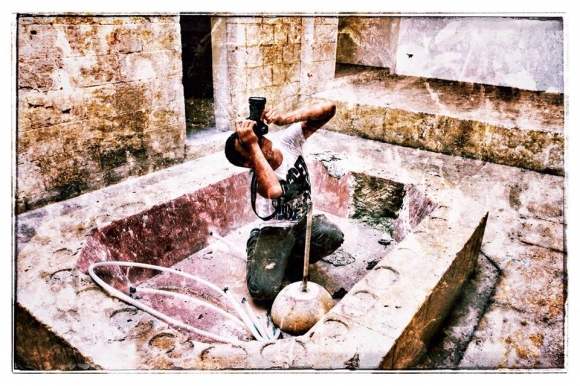

Molhem Barakat, 17, wanted to be a photographer so badly that he filed photos under an older photographer's name until he turned 18. Despite the increasingly violent Syrian civil war, Reuters agrees they began working with the kid from Aleppo in May of 2013. The agency furnished him with camera, body armor and ballistic helmet and began paying him for his photos of the conflict.

Barakat died just seven months later.

He was killed during a battle in Aleppo alongside his older brother, a rebel in a local brigade. The camera provided to Barakat by Reuters was found covered in his blood.

The Syrian conflict has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and forced millions to seek shelter in neighboring countries. According to Foreign Policy, 61 photographers and journalists have died. Dozens more have been kidnapped or gone missing. Most of these are Syrian; foreign reporters consider the war too dangerous, covering it instead from Lebanon or Turkey.

Even amidst all this death and tragedy, Barakat’s loss has struck a nerve among war correspondents, many of whom are criticizing Reuters for relying on young photographers like Barakat to cover the war and for inadequately protecting them. Other observers have questioned Reuters decision to work with a journalist like Barakat with known affiliation to a rebel brigade.

Former Baghdad bureau chief Andrew MacGregor Marshall rewrote Reuters's war zone safety guidelines in 2008. He says that Reuters violated its own policy that prohibits staff or freelance employees from accompanying armed people "…without the explicit authorization of [their] bureau chief or regional managing editor."

He also noted that the policy advises reporters to "[n]ever cross the line, or give the appearance of crossing the line, between the role of journalist as impartial observer and that of participant in a conflict."

Molhem Barakat’s story began in the winter of 2012 when Adnan Haddad, a Syrian activist, enlisted him to work in the pro-uprising Aleppo Media Center. Haddad said of him, "I was there the moment he grabbed the first camera -- I still remember it. It was a Sony HD Handycam, and he was just so good with it."

While Barakat loved photography, he also needed the job to help support his family. As a Reuters’s stringer he appears to have worked unsupervised, going into combat situations that would horrify more experienced war correspondents. For a while things went well. His images traveled around the world, appearing in major publications such as the New York Times.

Although Reuters said in a statement that Barakat was 18 when they hired him, others dispute this. Adnan Haddad is sure he was not yet 18. On his Facebook page Barakat looks young and wears a charmingly goofy smile in dozens of selfies. Haddan notes too that Barakat was hardly an "…impartial, he was someone who want[ed] to serve the revolution."

For risking his life on a daily basis, notes photographer Stanislav Krupar, Barakat was paid as little as $100 for a set of 10 photos. The money helped keep his family out of poverty, but seems insignificant next to the eventual cost of Barakat's life. As Adnan Haddad told Foreign Policy magazine, “He was a young guy, a smart one, a very fast learner, and losing him like this -- for the sake of making a few hundred dollars -- is not worth it."

My friend Salim (not his real name) is a Syrian businessman who still travels to Damascus every few months. He speaks little of the war, but like many Syrians, feels helpless, caught in the middle of someone else’s nightmare. When I asked him what he thought of Barakat’s death he said pessimistically, “So many have died or fled, the war is becoming a war of the young against the younger.”

Haddan would agree. He told Foreign Policy, "There should be some kind of law during war and during conflicts that would prevent those organizations from using these underage activists, especially when it comes to money.”

Whether such a law is ever enacted it will come far too late for Molhem Barakat, a young kid with a dream, a camera, and -- thanks to Reuters -- a job.

(Via Foreign Policy. Molhel Barakat's Facebook page.)