AND MORE

Noiseware -- The Cure for High ISO

Editor

The Imaging Resource Digital Photography Newsletter

Review Date: March 2007

Last year several camera manufacturers significantly increased the sensitivity of their sensors even in some of the more affordable digicams. The push, so to speak, was to enable more options for available light photography -- and reduce any reliance on the pitiful little built-in flash.

ISO equivalents jumped from 400 to as high as 3200, with many models in the 1000 to 1600 range. And, for the most part, the increase was managed by turning up the volume, increasing the signal gain. In almost all cases, noise reduction was automatically applied to these high ISO images.

Our camera reviews, which include a full range of ISO shots, pointed out that above ISO 400, these images started to fall apart. Some cameras do better than others, but as manufacturers cram more photo sites on tiny digicam sensors, the problem is unavoidable. You really have to have a 3-megapixel digicam to avoid it.

This year the trend toward higher ISOs has continued. And image noise is starting to get noticed just like shutter lag once was: as a nuisance no one talks about.

THE PROBLEM | Back to Contents

It's true that you don't typically notice noise. When you review images on your LCD, the data has been resampled to fit on your screen so much the noise disappears. When you print images, the data is resampled again for one or another type of print screen, minimizing the effect.

But enlarge your image 200 percent (just double size, that is) in your favorite image editor and take a look at the sky. What you see may make you reach for the phone to call tech support. Instead of the smooth blue you think you shot, you've captured a mosaic of discount tiles that hardly match. And what's that magenta pixel doing in there?

That's noise. Data that didn't come from the scene.

But it's not a defect. It's a fact of digital life. Two facts, actually. Dark pixels in a lighter area are Luminance Noise. Off-colored pixels are Chrominance Noise.

They can be caused naturally by what's called dark current. Each sensor in your digicam's CCD is stimulated by light. The more light, the more electrical current. And this current is converted into data, somewhere between 0 and 255 units in an 8-bit channel. No light, no current. In theory.

Well, not in reality. The photo sites on a sensor are not uniform. Even without light, there may be a little current here and less there and none here. Where it's really noticeable, we call it a hot pixel. And it varies depending on the temperature of the sensor, too.

And even after the data is captured by the sensor, it is analyzed and processed by your camera's imaging chip. One of those processes, often optional, is noise reduction. On high ISO images, however, it often isn't optional. In-camera sharpening and increased contrast settings can, on the other hand, exaggerate noise.

Noise, as false data, is the great enemy of detail. It can often be difficult to distinguish between noise and detail in an image, too. And even worse, reducing noise can easily reduce detail. You have to bear in mind how your image will be viewed and how much detail you are trading for noise reduction.

TACKLING THE PROBLEM | Back to Contents

With so many new cameras hitting the store shelves last year, we took our turn reviewing a few digicams. We're big fans of natural light photography, hate those puny flashes that beam red-eye into everything and really don't mind a little noise. Reminds us of grainy film.

But other reviewers felt the high ISO shots were simply unusable. And we set out to see if there wasn't some tool that would make it feasible to shoot at high ISO and still expect quality results. It would be very welcome around here.

We had reviewed Nik Software's superb Dfine in our Aug. 8, 2003 issue. But that program requires a module for every camera you own. Not practical for a reviewer.

Recent versions of Photoshop have included a Noise Reduction filter that works very well on any image and we tried that for a while.

Then, at PMA last year, we sat down for a 15 minute demonstration of Imagenomic's Noiseware Professional (http://www.noiseware.com), a Photoshop plug-in to tackle the problem. What we liked immediately about Noiseware was that, unlike Dfine, it did not need a camera module and unlike Photoshop, it had a complete set of options for controlling noise. It also improves the more you use it.

Shortly after, a review copy arrived and we put Noiseware to work as a Photoshop plug-in. After several months of processing high ISO digicam images with it, we're ready to report on this tool, which has become indispensable to our workflow.

SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS | Back to Contents

We were impressed that Noiseware ran without a hiccup on the beta CS3 version of Photoshop. It's also compatible with Vista. One of the tribulations of upgrading your software is making sure your indispensable utilities are not out of phase. It seems Imagenomic is ahead of the curve there.

Windows requirements are for Windows 2000/XP/Vista and Mac OS requirements are for version 10.2.x through 10.4.x (PowerPC/Intel).

All systems require 256-MB free RAM, 10-MB free hard disk space and a 1024x768 pixel monitor.

Compatible host programs for the plug-in are Adobe Photoshop 7.0, CS, CS2 and CS3, Adobe Photoshop Elements 2/3/4/5, Corel Paint Shop Pro 9 and X, Corel Draw 10, 11 and 12, Microsoft Digital Image Suite 2006 and Ulead PhotoImpact XL, 10 and 11.

INSTALLATION | Back to Contents

We tested the $69.95 Professional version which supports Photoshop Actions, 16-bit channels and Smart Filters, unlike the $49.95 Standard version.

Installation from CD was straightforward, copying the plug-in to our Photoshop CS2 plug-in folder. To install it for CS3, we just copied the folder to CS3's plug-in folder. No problem. The plug-in appears at the bottom of the Filter menu in Photoshop.

There is a license key to install in the About Noiseware window. Then you're ready to roll.

KEY FEATURES | Back to Contents

Imagenomic touts four key features of Noiseware. While they're impressive, it's important to note that you don't have to master them to use the product. Basic use is as straightforward as using Photoshop's Reduce Noise filter, although it's a lot more helpful than Reduce Noise.

The four key features are:

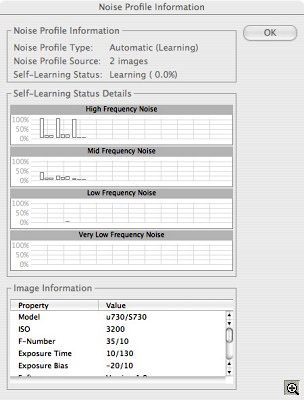

- IntelliProfile. This built-in expert system uses artificial intelligence to analyze and recognize noise patterns without relying on camera profiles. It can remember the results of its analysis, associating them with the Exif data, to "perfect its processing capabilities."

- Manual Profiling. Noiseware also provides for specifying custom image regions based on tone, color or detail for analysis.

- DetailGuard. This feature let's you safeguard image details during the filtering process with greater control than the global settings. It also protects the color fidelity of the image.

- Advanced Filter Controls. The controls available to fine-tune Noiseware include frequency, color and tonal range adjustment and noise reduction parameters as well as dedicated controls form luminance and color noise filtering. These are the sliders you use to adjust the default performance of the plug-in.

THE BASICS | Back to Contents

As we said, you don't have to fiddle around at the controls to enjoy Noiseware's power (even though it's hard to resist). Noiseware automatically analyzes the image, calculates a noise profile and processes the image when you start it up.

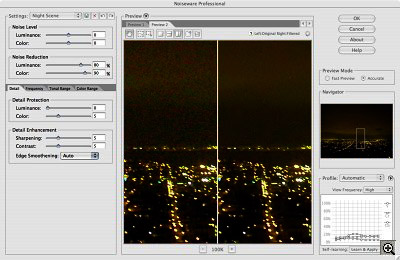

It uses a Default setting to do that, showing you the results in a preview window you can configure using zoom, split-screen and panning tools. The preview also mimics Photoshop filter behavior by showing the before state when you click and hold in the preview area.

It's worth emphasizing that the values you see when Noiseware displays its window are the result of its analysis of the image, not a starting point. Noiseware has already done its work behind the scenes, so you don't have to make adjustments as you might with Photoshop's Reduce Noise filter (which just remembers your last settings).

Sony T10 at ISO 1000. As shot (top), Noisware (middle), Photoshop (bottom).

It evaluates the whole image based on brightness level, graphing the amount of noise it finds for any given brightness level.

If you like what you see, you just have to click the OK button to apply it to your working image.

Presets. Default does a good job, but Noiseware can do even better if you apply one of its 14 predefined setting presets that are fine-tuned for specific kinds of images. You'll get smoother skies in your landscapes while preserving detail elsewhere in the image, for example, if you select the Landscape preset.

Changing presets is as simple as using the popup to pick another. And it's also a great introduction to using the advanced filter controls. Watch how each preset changes them and evaluate the results in the preview window.

Preview. The preview shows the results just seconds after you change values. You can zoom the preview from 25 to 800 percent. And you can split it in various ways to see before/after views or compare presets. You can also pan the image in the preview window. A small navigator window makes that very simple.

ADVANCED USE | Back to Contents

The plug-in window presents five sets of controls configured by each of the presets and you can fine tune any one of them at any time.

Fine Tuning. This tweaking starts with the Noise Level adjustment, whose slider can be adjusted for either Luminance of Color Noise from -20 to +20. With a negative value, you tell Noiseware there's really less noise than it found, while a positive value indicates there's more noise.

There's a similar set of sliders for Noise Reduction, with values ranging from zero to 100 percent. The lower the percentage, the more of the original image is included in the final output. The higher it is, the more of the filtered image appears. It's something like a fade control. Imagenomic notes that optimal Luminance values in most cases is between 60 and 70 percent, while optimal Color values are 80 to 90 percent.

Noiseware identifies different frequencies of image noise. High frequency noise is contained in individual pixels. Low frequency noise affects a group of pixels, like color banding and blotches. High frequency noise, Imagenomic suggests, can be ignored without affecting image quality but low frequency noise can significantly degrade an image. So Noiseware has a Frequency tab with sliders for four different frequencies of noise: High, Mid, Low and Very Low. Values range from -20 to +20.

A Tonal Range tab lets you set the noise level and reduction amounts for shadows, mid-tone and highlights, again within a range of -20 to +20 for the level and zero to 100 percent for the amount.

And a Color Range tab lets you do the same thing over seven color ranges: Reds, Yellows, Greens, Cyans, Blues, Magentas and Neutrals.

You simply have your pick of controls to address whatever issue you identify in the corrected image.

The first tab in this set, however, is Detail, which provides Detail Protection with Luminance and Color sliders whose values can run from zero to 20. The Detail Enhancement pane below it provides Sharpening (unsharp masking with oversharpening controls) and Contrast sliders whose values can also be set from zero to 20. There's also a popup to set the amount of Edge Smoothing among Auto, High, Normal and Low.

Setting Edge Smoothing to a lower setting can restore a more natural look to an otherwise over-processed image. The Low setting preserves more detail, as for a landscape shot, while a High setting provides more smoothing, as for a portrait.

You can undo and redo any filter operation and you can save your own final adjustments as a filter preset to apply to other similar images.

Manual Adjustment. In addition to global fine-tuning, you can restrict Noiseware's analysis to specific parts of the image. The Single Selection tool lets you indicate which part of the image to use for analysis before switching to the Multiple Regions Selection tool that lets you add up to 10 others.

Evaluating Results. Switching between presets and even just twiddling with sliders can make such dramatic and subtle changes to an image that it can be hard to see just what happened. Fortunately, Noiseware has a couple of tricks up its sleeve to help you evaluation results.

Multiple Previews allow you to add a preview and set the effect for just that preview. You can add up to 20 of them, so you can see the effect of a whole range of presets before applying one to your image.

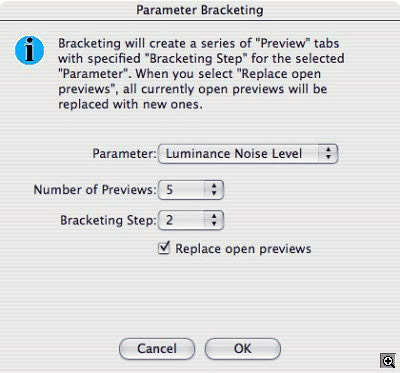

When you have a clue about which approach to use but aren't sure how much of it to apply, Noiseware's Bracketing comes in handy, quickly previewing three options with custom intervals for any parameter you want to compare. You can, for example, create three, five or seven previews showing various Luminance Noise Level adjustments with 2 to 10 values between each step. Or 5 to 30 percent adjustments for each step on Noise Reduction previews.

Self Learning. Noiseware can improve its noise detection with each image it analyzes when you enable its self-learning mode.

The program associates its analysis of the noise in an image's tonal range, frequency and channel with the Exif data recorded at capture that reveal what camera took the shot and what the shooting conditions were (like ISO, f-stop, shutter speed, white balance, etc.). Noiseware's self-learning also supports Adobe Camera Raw data.

So, for the most accurate results, it's a good idea to run Noiseware on the image fresh from the camera, rather than after you've made tone and color adjustments.

The effect of this self-learning can easily be omitted from analysis for any particular image. And if the Exif data isn't available to Noiseware, it will disable self-learning.

IN ACTION | Back to Contents

Our original ambition was to find a way to salvage high ISO images shot by digicams, which have a higher density of photo sites on their small sensors than dSLRs. In other words, we expected to run the filter only on images with noise.

And that proved to be a bright idea. Noiseware assumes there's noise to be cleaned up in any image you throw at it. So our gorgeous 11-MB dSLR landscapes shot at low ISO with little real noise actually suffered a loss of detail when we ran them through Noiseware, even when we protected the detail.

But Noiseware performed miracles on the high ISO images we threw at it. These were generally between ISO 800 and ISO 3200 using large megapixel digicams (from 6-10 megapixels) and the occasional dSLR shooting at 1600.

And the miracles Noiseware performed in our tests were done with the default settings on subjects that varied from low light macro shots to museums to nightscapes.

Two points about that. First, we hadn't built up much a knowledge base for Noiseware to profit from self-learning, having done just a dozen or so high ISO samples for camera reviews. And secondly, any quibbles we might have had with any of these results would have been our starting place for fine tuning.

When we did fine tune, we really didn't improve much on the default treatment. Maybe that's just us, but it could also be that the program hits very close to a bullseye for most images.

The Reduction sliders let you fade the effect, as we pointed out, but you can also do that with layers, which gives you a bit more flexibility. Just duplicate the layer, run the filter on the duplicate layer and change the opacity of the duplicate layer until you like the mix of noisy original and smoothed duplicate. If your print surprises you, you can just change the opacity and try again.

We expected Noiseware to help high ISO images, but it's also handy for images that require shadow detail recovery. Uwe Steinmueller has written an article (http://www.outbackphoto.com/workflow/wf_68/essay.html) detailing his technique for using Noiseware on just the darker areas of an image after recovering shadow detail using Photoshop's Highlight/Shadow command.

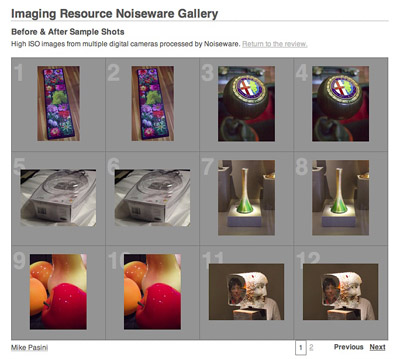

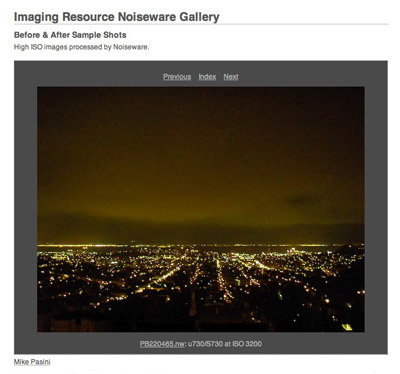

THE GALLERY | Back to Contents

The proof of Noiseware's performance, however, is in the images. So we've built a gallery of sample images. Images were shot from a variety of cameras including a Casio EX-Z1000, Sony DSC-T10, FinePix S9100, Nikon Coolpix S7c, Nikon D70s, Panasonic DMC-TZ1, Olympus Stylus 730 and Sony DSC-W30.

The gallery includes 12 pairs of images. Each pair includes the camera original and the default Noiseware version (with a "nw" appended to the file name). Click an image displayed on the index page to see a full screen version of it. From there, use the Previous or Next links to compare versions.

Note that the full screen version is a downsampled version of the original, full resolution file. Even at this size, though, you can see the difference Noiseware makes. The file name, camera model and ISO setting are displayed below the image (if available).

Full Screen. The filename under the picture links to the full resolution version. The model name and ISO setting are also listed in the caption.

To see the full resolution image, just click on the underlined file name at the bottom of the single image display. The full resolution image will pop up in a separate window. There is a different large window for originals and the Noiseware version so you can compare the two full resolution images on your monitor.

CONCLUSION | Back to Contents

After shutter lag (which has mainly been addressed), the scourge of digital photography has been red-eye. You can't squeeze a flash on a tiny camera and expect to avoid it. But recently manufacturers have taken a different approach, increasing the ISO sensitivity of their cameras. The cost of that approach is increased image noise, some of which disappears in a small print but much of which is evident even when just displaying the image on your computer monitor.

Enter Noiseware. At its default settings, the plug-in analyzes an image for noise and corrects it, preserving most of the detail. From there you can fine tune the adjustments to remove more noise or protect more detail in parts or all of the image. And you can create an Action for batch processing whole shoots, if you want.

The effect is to restore image quality to high ISO shots making you even less dependent on that little flash. And that's why even amateur photographers will find it indispensable. Pros won't mind that either, but they'll find other uses for this capable tool, like removing noise from recovered shadow detail, too.