The Nearly Forgotten Mother of Modern American Photography, Gertrude Käsebier.

posted Saturday, May 12, 2012 at 9:05 PM EST

American photography has many fathers, like Mathew Brady and Alfred Stieglitz, but there was just one woman who was its mother, Gertrude Käsebier. Not only was she one of the first American women to have a successful career as a photographer, but she was one of the first photographers anywhere to focus on the family. In her timeless images of mothers and children, she helped to shape the modern way we photograph today. In her day, she was famous and influential, a model for young women photographers at a time when proper women were supposed to stay home and tend to their families. One of the women she influenced was Imogen Cunningham, who I was lucky enough to meet in the 1970s.

American photography has many fathers, like Mathew Brady and Alfred Stieglitz, but there was just one woman who was its mother, Gertrude Käsebier. Not only was she one of the first American women to have a successful career as a photographer, but she was one of the first photographers anywhere to focus on the family. In her timeless images of mothers and children, she helped to shape the modern way we photograph today. In her day, she was famous and influential, a model for young women photographers at a time when proper women were supposed to stay home and tend to their families. One of the women she influenced was Imogen Cunningham, who I was lucky enough to meet in the 1970s.

Käsebier was a true child of the American frontier, born Gertrude Stanton in the Iowa town of Fort Des Moines--now known simply as Des Moines--in 1854. Her father moved the family to Golden, Colorado, where they lived until his death in 1864. The remaining family members moved back East, where Gertrude went to school and then, at the age of twenty-two, married wealthy Brooklyn, New York businessman Eduard Käsebier. The couple quickly had three children, and the family moved to the wide-open spaces of New Durham, New Jersey for a healthier lifestyle. However, the marriage did not work out and in 1880 the couple separated. Käsebier described her marriage thus:

"If my husband has gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible... Nothing was ever good enough for him."

Despite their living separately her husband continued to support her, and although he objected when in 1889 she moved back to Brooklyn with the children, he didn't withdraw his support. This allowed her to move in New York's social circles and to take art classes at the new Pratt Institute of Art and Design.

|

Käsebier's portrait of a teenage Evelyn Nesbit, whose striking beauty was to make her one of New York's most popular models. Photo by Gertrude Käsebier, via Shorpy. |

In 1896, when facing financial difficulties, Gertrude got a job as an assistant to Brooklyn portrait photographer Samuel H. Lifshey, where she learned how to run a studio and work as a professional photographer. Within a year, she was exhibiting her photographs around New York, and when asked to speak at the Photographic Society of Philadelphia in 1897, she told her audience:

"I earnestly advise women of artistic tastes to train for the unworked field of modern photography. It seems to be especially adapted to them, and the few who have entered it are meeting a gratifying and profitable success."

Käsebier worked as a portrait photographer and artist, and was soon seen as a rival to Alfred Stieglitz. As one critic wrote:

"...a year ago Käsebier's name was practically unknown in the photographic world...Today that name stands first and unrivaled..."

|

Mina Turner and her cousin Elizabeth enjoy lollipops at a home in Waban, Massachusetts, as an unidentified woman watches from the shadows. Photo by Gertrude Käsebier, via Shorpy. |

At the turn of the century, American photography was dominated by "pictorialism", whose adherents believed that the photographer had to manipulate images, using soft focus, printing in colors other than black-and-white, or adding visible brush strokes and other surface manipulation to the photograph.

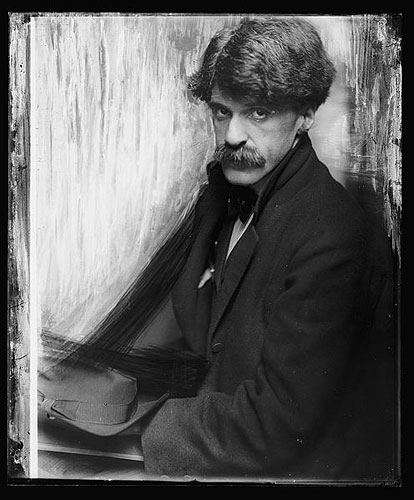

Stieglitz included Käsebier as a founding member of the Photo-Secession, a group that argued for a more natural, less manipulated photograph. In 1899, he published five of her photos, declaring her "beyond dispute, the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day." And then in 1903, he published six of her images in the first issue of Camera Work.

|

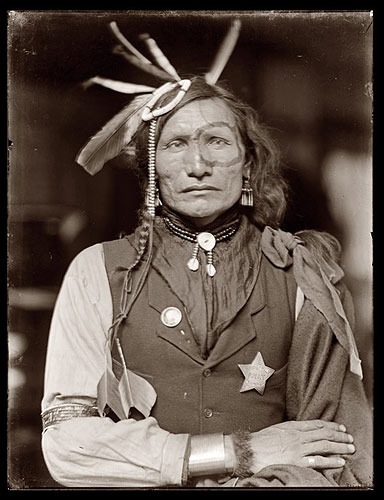

Iron White Man, a Sioux Indian in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. Photo by Gertrude Käsebier, via Ghost Cowboy. |

At the end of the 19th century, Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show was touring the world, performing for millions of people. Bill's show presented an idealized vision of the American frontier, which by this time had ended decades earlier with the building of the railroads. Among the show's sharpshooters and cowboys, Bill had a cast of Native Americans who "reenacted" famous scenes from the "taming" of the West, like Custer's Last Stand.

When Käsebier saw the show, it reminded of her own childhood, and one day she went to visit the "Indian" encampment at the show venue. Responding to what she saw, she began to photograph the faces of the Wild West show's Native Americans. Unlike the images of Edward Curtis, Käsebier focused on the emotions and expressiveness of her subjects. Where Curtis saw noble savages fading into history, she saw individuals who had lost their way of life.

|

Gertrude also turned her lens on fellow photographers, including Alfred Stieglitz. Photo by Gertrude Käsebier, via the blog of Andrei Venghiac. |

In 1900, Käsebier was called by Steiglitz "the foremost professional photographer in the United States." Her work inspired other women like Imogen Cunningham and Laura Gilpin to become photographers, and she helped guide photography away from the manipulated imagery of pictorialism. Today, she is hardly remembered. Nonetheless, whether we aware of it or not, we are all the children of Gertrude Käsebier.

To see more photos by Gertrude Kasebier, visit the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, vintage photo website Shorpy, or watch the short film Masters of Photography - Gertrude Käsebier below.

|

|

|

The short film 'Masters of Photography - Gertrude Käsebier' recaps the lifetime of the mother of American Photography, and shows some of her most memorable works. Video by Masters of Photography, courtesy YouTube. |