Through African eyes: Adolphus Opara’s stunning documentary portraits

posted Thursday, September 6, 2012 at 10:47 AM EST

When I first saw the work of Nigerian documentary photographer Adolphus Opara, the sheer beauty of his work -- especially his strong sense of color -- startled me. In particular, the 20-image portfolio titled "Emissaries of an Iconic Religion" showcases the depths of his talent, where his warm, intimate portraits of the exotic Yorùbá chief-priests and priestesses cut across the borders of geography, culture and belief.

Rarely have I seen such a marvelous blend of photojournalism, color and emotion, and I realized I needed to learn more about Opara and his work. So I contacted him online to get a deeper glimpse into what makes him tick as a photographer and artist.

Opara works and lives in Lagos, Nigeria's most populated city, and he describes himself as "first and foremost a storyteller." Born in 1981, he studied computer science in college and then worked as a graphic designer for the Nimbus studio and art gallery. At first, he did not have any interest in photography.

"I bought my first film camera in early 2005," Opara told me. "But I threw it away after a month because the pictures I took were so terrible."

However, his attitude changed when his friend, documentary photographer George Osodi, sold him a Fuji FinePix S3 Pro. Opara was fascinated by the camera, and set out on a road trip to Senegal, “shooting all the way, totally trigger crazy."

Today, Opara shoots images of the world and people he sees around him. "More than anywhere else, Africa is particularly tied up with its ethnic, cultural, religious and other identities," Opara said. Through his photography, he strives to capture the diversity of those competing identities.

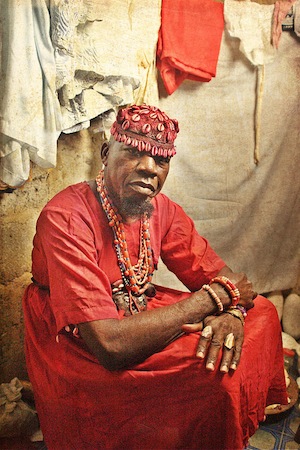

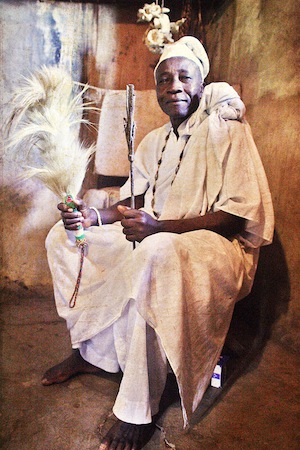

(Above Left) Here is a good example, for me, of how Opara uses color to hold a photo together. The red cloth above the priest’s head balances the red of his clothing. Cover the cloth with your finger and you will see how the picture loses this balance. (Above Right) I like this photograph’s monochromatic look. But, notice how Opara still has a hint of daylight blue and little bits of color on the handle in the priest’s right hand to keep the warm tones from overwhelming the image.

Photos copyright Adolphus Opara. All images used by permission of the photographer.

"I never plan anything," Opara said. "I follow my instincts and often my projects start off as quite small, intimate explorations that grow into something more. By the end, there is always a bigger story underneath about Nigeria or Africa, and about the forces that shape us either from within or from the outside."

Religion is one of those forces that Opara was interested in exploring, and Nigeria is a nation of many faiths. The streets of Lagos are lined with storefront churches that jostle up against mosques and native religion shops. Recently, in some parts of the country’s north, religious conflict has broken out.

The “Emissaries” project grew from a chance meeting Opara had with a friend who thought the local Yorùbá religion was something bad, something barbaric, something like voodoo. Opara saw his friend's reaction as an opportunity to alter the misperceptions the outside world has about Africans; he believes the foreign press only portrays his people as unwashed primitives or victims of war, famine and catastrophe. "As someone who trained and works as a journalist, I can see why others go to cover disaster and war, but there is another Africa, many other Africas," Opara said.

Opara tries to reveal that "other" Africa by portraying his subjects as fully formed, complex people -- never as one-dimensional stereotypes. In "Emissaries," Opara succeeded in creating images of the Yorùbá believers that were not only filled with color and intimacy, but also with gravitas and dignity.

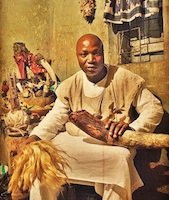

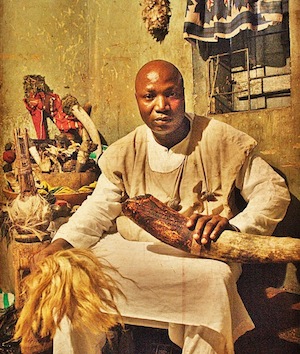

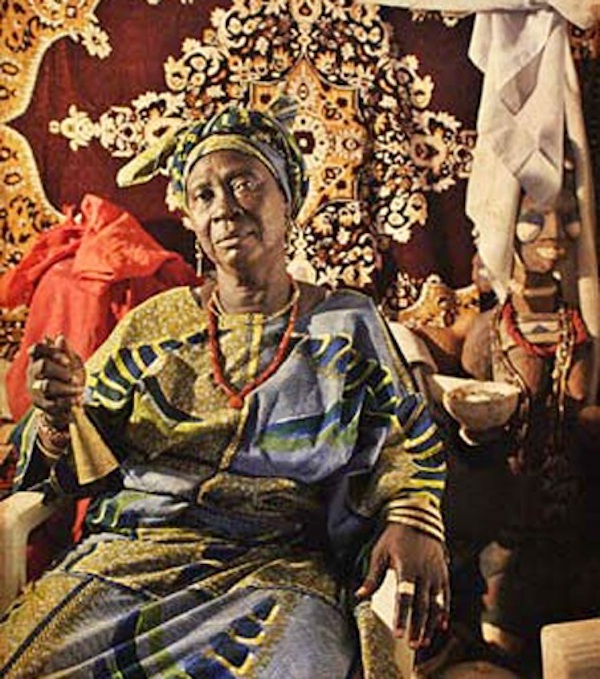

(Above Left) Again, a photo filled with rich, warm tones and Opara cleverly uses red to focus our attention. My eye is drawn to the priest’s face, then the tusk in his hand. It points to the red object in the corner, that then points my eye back to the man’s face. (Above Right) I love both the busyness of the elements in this photo and the way the tones work together. I especially like how the rumpled dress of the priestess is echoed in the wall decoration behind her, as well as the counterpoint between the smile on the face of the figure and the woman's expression.

Photos copyright Adolphus Opara. All images used by permission of the photographer.

As a working photojournalist myself, I know capturing the true essence of a person or moment in time is one of the hardest goals to achieve. And Opara pulls it off repeatedly and elegantly in this series and others. I love how the muted but warm colors he brought forth in "Emissaries" give the portraits a painted quality that stylistically unites them while adding incredible intimacy.

Opara's philosophical approach to photography is almost as important as his skill. Many of us are “single-shot” photographers, always looking for that one photo that tells the story. But Opara strives to do more. "As much as I believe in the power of a single image, I believe even stronger that I can drive home my points better with multiple images that tell complete visual stories,” he said.

Besides the Yorùbá priests, Opara has shot portfolios on a range of topics, from the brutal realities of the Lagos meat market to the grace of the men who play “Rugball” (a combination of rugby and soccer) on the city’s beaches. You can see the full range of Opara's work at www.adolphusopara.com, where you'll find that he's as adept at shooting in black and white as he is in color.

It's always exciting for me to discover a talent such as Adolphus Opara, who is part of a new generation of photographers. Raised on color images and digital cameras, Opara and other young shooters bring a fresh vision to what photojournalism can be.

Nigerian Adolphus Opara is part of a new generation of photographers who grew up on color images and digital cameras. I find his varied portfolios of work, from portraits to captured moments, simply stunning.

Photo courtesy of Tuoyo Omagba.