Does photojournalism matter? You bet it does, just look at W. Eugene Smith’s work

posted Tuesday, September 11, 2012 at 11:14 AM EST

“The world does not conveniently fit into the format of a 35mm camera.” - W. Eugene Smith.

Over the Labor Day weekend, I found a marvelous, short video about W. Eugene Smith, entitled “Minimata by W.Eugene Smith.” (See below.) Smith was one of the best American photojournalists ever, and this video is a reminder of his commitment to photography and his struggle to get work it published.

Over the last week of August and the Labor Day weekend, “Visa pour l’image” was held in Perpignan, France. This is the annual, international festival of photojournalism and I was lucky enough to have an exhibit of pictures there in 2003. Even back then, the reports of the impending “death of photojournalism” were rampant.

As newspapers and magazines struggled to survive by moving online, the story went, serious photojournalism would be lost in the cacophony of free iPhone images. Editors would no longer have a budget to send photographers off to cover stories and that would be that.

Nonetheless, photojournalism has survived and as demonstrated by the work of young photographers like Adolphus Opara, it is thriving. The reason is simple, photojournalists do not need editors to assign stories, they find subjects themselves. And that, is in part of the legacy of W. (William) Eugene Smith. His black-and-white images stand as a monument to the power of photojournalism.

The poisoning of Minimata Bay

The video on YouTube is a blend of Gene Smith’s still photography and TV news footage. Narrated by Smith’s widow Aileen, it tells the story of the mercury poisoning of a small Japanese fishing village, which was adjacent to a large industrial plant.

For years, the Chisso Company had dumped waste into Minimata Bay, resulting in extremely high levels of mercury and other metals in the fish that were central to the villagers’ diet. This led to cancer and birth defects among them. They were now suing the company for the damage to their health and when Smith read about this, he and Aileen moved to Japan and spent two years (1971-1973) documenting the story.

No one assigned him to do it.

Smith’s commitment to photography earned him a reputation for being difficult to work. He was uncompromising about his work. For example, when Life magazine sent him for a week to photograph Dr. Albert Schweitzer in Africa, he decided to stay for months. When he finally did return, he demanded to have a say in the story layout.

Smith approached the Minimata tragedy in the same way. Rather than a quick visit, he moved in and over time become part of the village. This allowed him to shoot some of the most beautiful and powerful black-and-white documentary images ever made.

Many are seen in the video and this provided me a chance to see how the still images stood up against the TV footage. For example, mercury affects muscle control and in one video, shot at a rehabilitation center, a poisoning victim was relearning to walk. It is a typical “rehab” video, the man laboriously moving one leg at a time, and the camera a disinterested viewer at some distance.

The photo Smith took at the same time is shown after the video. Now we are next to the man, looking into his eyes and seeing his anguished face. We are no longer disinterested spectators we share the horror of what has happened to him and his determination to walk again.

Images with impact

Like all of Smith’s work, these images have impact and stopping power and that raises them above other newspaper or magazine work. But, many editors were reluctant to use Smith’s images for fear they would disturb readers or interrupt the flow of the magazine; reducing the attention given to the ads.

As Smith’s images of Minimata began to circulate, there was growing concern at the Chisso plant. In January 1972, while photographing, Smith was attacked by a group of workers. Badly injured, he spent a long time in hospital and lost most of the vision in one eye.

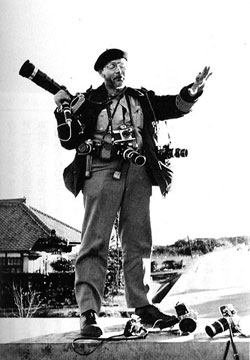

I met Gene Smith, as he was returning to New York and still recovering. He had arranged a few days layover in Seattle, at a friend’s, a photographer I knew. After Smith arrived, I got a call from my friend saying that Smith would like to meet with some of the local photojournalists the next evening and talk photography with him. This was very exciting for me; Smith was one of my idols and I knew his images by heart, from the steelworkers of Pittsburgh (1955-1958) to the asylum inmates of Haiti (1958-1959).

That evening we sat in a circle around him. He spoke softly and moved slowly, still feeling the effects of the attack. Plastic cups filled with wine were passed around, while Smith talked about Minimata. The case was still in the courts, he said, and although there was hope for a monetary settlement, the environmental damage to the Bay and the people would last for generations.

He spoke about his photography, and about the responsibility, each of us had to use our talent for good, to make a difference. This made us uncomfortable as we were just working shooters trying to make a living. We did not know how to go out and do what he did, we were afraid to just go off and do a story. Smith saw it in our eyes and sipped a little more wine. Cradling the cup in his hands, he leaned his injured body forward and he stared silently at the floor for a moment. Then looking up, he said, “Never be afraid to do what’s right.”