The rather sad story of the father of American photography

posted Thursday, October 4, 2012 at 4:33 PM EDT

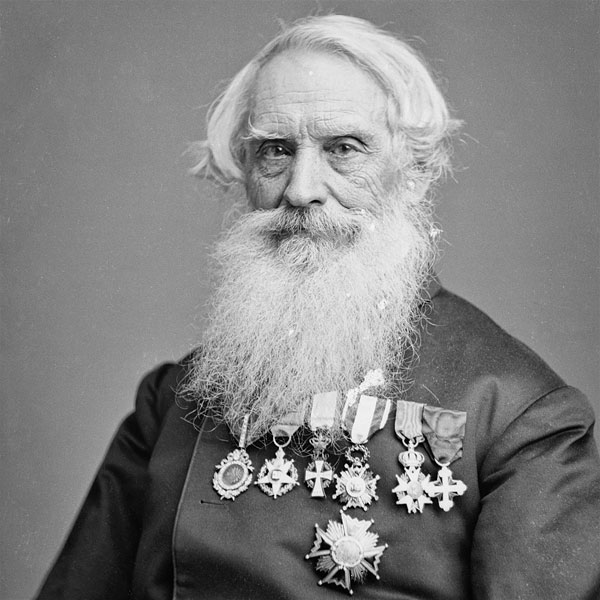

Samuel Morse: The man who (almost) never succeeded

It’s been a long time since I did a photography history article. I generally prefer the early days of photography. People just were--I don’t know, more--back then. There was more lying, more backstabbing, more drama, and more originality. You name it; they did more of it.

In my various readings, which I do far too much of, I learned a bit about Samuel Morse and became fascinated. This guy had more careers than I have. (Hey, some of those careers I wanted to leave. Don’t be tacky.) At various times he was a preacher, a painter, a professor, an inventor, a photographer, and a politician.

But when I looked a little deeper, I found he wasn’t a Renaissance-type Polymath as I had assumed. Morse was an argumentative, whining man who failed at one career after another, fought with and sued (or was sued by) virtually every associate he ever had, and played the poor-pitiful-me victim card at every turn. He succeeded at almost everything he did for a while, then failed miserably and left to do something else.

He is recognized as the inventor of the telegraph, which he really wasn’t, and the originator of Morse code, which he probably was. On one of his many career side-trips he also had a large role in bringing photography to the U. S. It is largely because of Morse that American photography took a leading role in the mid-1800s. That wasn’t really his intention, though. He spent far more time and energy telling everyone he had done it than he actually spent in doing it.

He was an ugly man, as my sainted mother would say in her best Steel Magnolia voice. In the South ugly doesn’t refer so much to physical appearance as it does to personality. When I told the story of Petzval and Voigtlander it was a bit tragic: a great inventor robbed of his just rewards by a sneaky businessman. That happened to Morse, too, but he was his own worst enemy.

Morse’s Origins

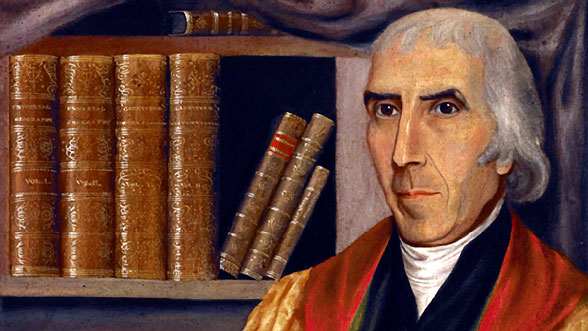

Morse probably came by his rather opinionated personality rather naturally. He was born in 1791, the eldest son of Jedidiah Morse. As you would expect, with a name like Jedidiah, Papa Morse was a fire breathing, New England Congregationalist Minister. He also wrote most of the Geography books that originated in America in the decades around 1800, and was widely known as ‘the Father of American Geography’.

Jedidiah followed the ‘Often wrong, never in doubt’ school of thinking, with a nice dash of paranoia thrown in. He spent most of his time fighting Unitarianism, Popery, Freemasonry, and anything else he considered a threat to America. He knew most of the founding fathers of America, idolizing Washington but despising Adams and Jefferson as Jacobinists.

Samuel Morse spent most of his youth at various boarding schools, which wasn't unusual in the day, and eventually attended Yale College. Yale was largely known for two things: training Puritanical clergy--his parent’s hope for Samuel--and experimentation in newfangled sciences like electricity. In those days, Yale was largely a reaction to the more liberal Harvard College, with Yale’s Puritan roots showing in rules against ‘card playing, tavern going, and acts of disobedience to college authorities’.

Just like colleges today, the rules seemed put in place to mostly reassure the parents paying tuition. Morse played cards, hung out at the local tavern, went on ‘shooting parties’ with his classmates, and was at first an indifferent student. Like most college students, his letters home begged for more money; his parent’s responses were ‘not with those grades, Sammy’. Morse became a better student; his parents forked over more cash.

After putting his parents in debt obtaining his degree, Samuel did what children have done after graduation forever: he decided he really didn’t like the field his degree prepared him for. He wanted to be a painter--canvas, that is, not houses. He had been a self-taught painter for some time and thought it would be a marvelous idea if he went to England to study painting for three years with two prominent American painters of the day, Washington Alliston and Benjamin West.

It somehow never occurred to Samuel that there was a reason Benjamin West, the greatest early American painter, lived in London and made his living painting pictures of King George and Horatio Nelson — there was no market for fine art in America at the time. Jedidiah was aware of this and refused Samuel’s request to study in England, setting him up in a nice apprenticeship with a book publisher.

Morse dutifully followed his father’s directions and took the job his father arranged at a Boston publisher. He proceeded to write home weekly that he was completely miserable, had no reason to live, but he would die happily knowing he had followed his family’s wishes. After some months of this Jedidiah was willing to pay any price to get Samuel out of his hair, so off to study art in England he went.

The Painting Years

Morse was quite successful in his art studies, producing at least one critically acclaimed painting, Dying Hercules. He also managed to gain admittance to the Royal Academy in 1811, which probably had the added benefits of driving his Anglophobic father completely insane. Remember, the war of 1812 was right around the corner, and so the U. S. and Britain weren’t exactly best friends at the time.

Morse returned to America in 1815 and did quite well as a painter — for a while. He was commissioned to paint portraits of John Adams, James Monroe, and the Marquis de Lafayette, among others. But commissions dried up as the American economy soured. For a decade Morse struggled financially. He moved constantly, taught students in Charleston and New York, and took commissions where he could get them.

He married, but his wife and children lived with his parents or other relatives while he worked to establish himself. However, even when Morse was doing well--at one time he had a large house in New York City and was regularly sending money home--he never sent for his family. When his wife died suddenly in 1825, Morse sent the children to live with various relatives and rarely visited them.

He was crushed that he was turned down to paint one of four scenes for the new United States Capital building. Instead, he painted a huge scene of the capital itself, hoping to draw large crowds to its exhibition, but this failed financially.

In 1829 he decided he needed further study in Europe. He took commissions to paint copies of various famous paintings, and left to spend the next three years in Italy and France. Toward the end of his stay he spent several months painting his masterpiece, The Gallery of the Louvre, expecting to sell it for a large sum when he returned to America. As usual, Morse was disappointed. The exhibition of the painting drew meager crowds and he sold it eventually for $1500.

The Early Telegraph Years

Morse returned to America on board the sailing ship Sully in 1832. During the voyage he had lengthy discussions with Dr. Thomas Jackson regarding the ability of electricity to pass a current instantaneously through a wire over great distances. After arriving back in America he began to work on a device using batteries and copper wire that would transmit a signal over distances.

Having no real scientific education, Morse spent a lot of time with Professor Leonard Gale who helped him develop a power source and the electromagnetic relays that let the system work over long distances. Having no practical engineering background, nor any money, he partnered with Alfred Vail, whose family owned a large machine shop and provided both funds and equipment to develop Morse’s ideas.

Morse and Vail exhibited a working device in 1838. Rather than using the series of dots and dashes that eventually became Morse code, they sent a series of numbers. The numbers each correlated to a word in a large dictionary. The number 29 might mean ‘horse’ while 162 might be ‘rider’, etc. (Morse felt selling the dictionary would be a major profit for his new invention.)

Finding no one in America was interested in purchasing his invention, Morse travelled back to Europe hoping to sell it there. Once again he was unsuccessful. Great Britain already had a working (in a limited way), patented telegraph system developed by Sir William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone. The system wasn’t nearly as good as the Morse system, which required just a single wire and was much simpler. On the other hand, it was Britain and Cooke and Wheatstone were British.

A similar reception awaited in Europe where Gauss and Weber had developed a telegraph system that Carl Steinheil had deployed in Munich. Again, the system was more complex than Morse’s, but the Germans weren’t interested in paying Morse when they already had a system in place, even though it was a limited system.

As an aside, in 1839 Steinheil became the first German to use Daguerre’s newfangled camera system. (Can you believe I got this far without an aside?) Within a few months he had developed a method to create a negative image and multiple positive prints on paper, similar to Talbot’s photographs. In the 1850s he founded the Steinhill optical works and his son, Hugo, developed some of the most important camera lenses of the 1800s.

Apparently the closest Morse came to selling his system while in Europe was to Russia, who found it attractive largely because it wasn’t British or German. But the Czars spent all their money on Faberge Eggs and such in those days, and never got around to purchasing the telegraph.

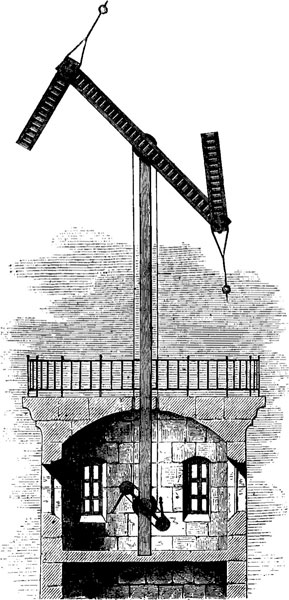

The French also took a look but they already had a high tech system in place: they had built a series of small towers a few miles apart, each of which had moveable wooden arms on top. The arms were controlled by ropes, sending a series of semaphore signals. The French felt this was far more reliable than some signal traveling through electrical wires. They sort of glossed over things like darkness, fog, rain, and wind; all of which made their system shut down.

Morse returned to America broke and unsuccessful. But his trip to Europe wasn’t entirely useless.

Photography

While in France in 1838, the American Ambassador arranged a meeting with a French inventor and showman, Louis Daguerre. Daguerre treated Morse to a show at his Diorama, demonstrated his new camera, and showed a number of photographs, which impressed Morse greatly. Morse returned the favor by demonstrating the telegraph to Daguerre. (It was during this demonstration that Daguerre’s Diorama Theater burnt down, so apparently Morse’s bad financial luck spread to people around him.)

Daguerre agreed to furnish Morse with all of the documentation for his process as soon as the French Government agreed to buy the photographic invention. Morse received his copy of Daguerre’s book in the summer of 1839 and built his own Daguerreotype camera. Morse, having no money as usual, talked his two brothers into removing the roof of their six story newspaper building and replacing it with a skylight, allowing him to have the first photography studio in America.

Morse partnered with Dr. John Draper, a Professor of Chemistry at New York University. Draper’s chemical background allowed him to make improvements to Daguerre’s development process. By 1840 he had shortened exposure times enough to take actual portraits, something Daguerre had felt could never be accomplished. He was also the first man to photograph the moon and the first American to take photographs through a microscope.

Morse and Draper also opened a Daguerreian studio and classroom in 1840, assisted by Samuel Broadbent. While it seems Morse did not have great success in his portrait business, he took students and taught them the processes involved for a fee of $25 to $50. He made a reasonable living this way for several years.

In addition to Broadbent, Morse trained Mathew Brady, Albert Sands Southworth, Edward Anthony, and Jeremiah Gurney. These men went on to become America’s foremost early photographers.

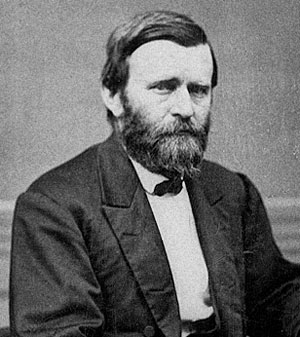

Matthew Brady’s Civil War photographs were the origin of photojournalism. It is Brady’s photographs of Abraham Lincoln that provide the images on the Penny and $5 bill. Brady made almost every surviving photograph of American Civil War generals, both Union and Confederate.

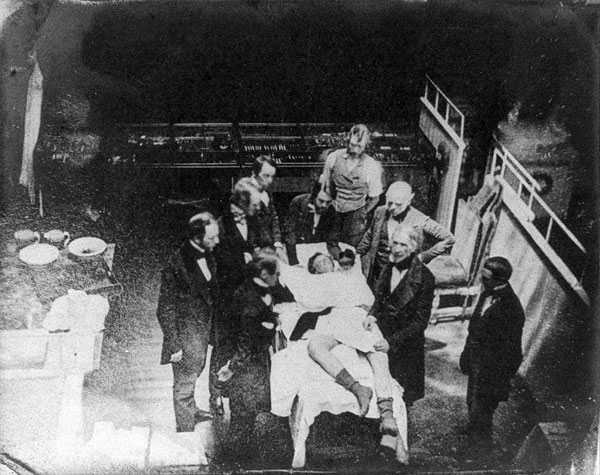

Broadbent opened the first photographic studios in Philadelphia and Atlanta. Southworth did the same in Boston where he additionally was the photographer for the Massachusetts General Hospital, recording operating room scenes including the first surgeries under anesthesia.

Anthony became the first to use photographs as legal evidence, submitting landscapes of the boundary between the U. S. and Canada to demonstrate landmarks. He later founded the E. & H. T. Anthony & Company, which was the largest distributor of photography equipment in the U. S. until Kodak changed the market. Oddly enough, Matthew Brady spent so much money making his Civil War photographs that his plates all became the property of E & H. T. Anthony & Co. when he defaulted on payment for his photographic supplies.

Gurney was probably the best-known American portrait photographer of the 1850s and 60s. He was one of the first American photographers to exhibit in Britain and Europe. It was his exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1853 that led magazines of the day to state, “It is generally understood that the best daguerreotypes are produced in the United States”.

Like so many of his occupations, Morse was not particularly successful in his own photography business and he closed it within a few years, never to photograph again. His students, though, became the best-known American photographers of the Daguerreotype era and went on to train most of the American photographers of the next generation. Morse, therefore, has a legitimate claim to being the father of American photography.

Like his own children, though, he was an absentee father, having left the field shortly after its birth. And like many of his activities, Morse spent more time belittling the contributions of others and emphasizing his own than was appropriate.

He conveniently forgot the contributions of Dr. Draper, and in later life stated that he'd taught Draper, rather than properly crediting him as a co-investigator. Draper’s doctorate in chemistry makes it unlikely that Morse, as he later claimed, made most of the advances in the development process. Indeed, Morse was reminded that he himself took instruction from François Gouraud, an associate of Daguerre who came to America about the same time Morse began his photography experiments. When this was pointed out to him, he replied in print that he had spent considerable time unlearning what Gouraud wrongly taught.

The Rest of the Story

In 1843 Morse and his associates obtained a $30,000 grant from the U. S. Congress to create a telegraph line from Washington, D. C. to Baltimore, MD. It was hugely successful. Over the following years, the telegraph became perhaps the most important invention of the 1800s. Communication, which had been limited to the speed of a train or sailing ship, became almost instantaneous. Huge corporations, like Western Union and the Associated Press developed directly as a result of the new technology.

While Morse was successful, it seems unlikely he was ever happy. He was embroiled in dozens of lawsuits with various business partners and competitors for the remainder of his lifetime. While he became financially successful, it was largely because he had received 5,000 shares of the Western Union Company when it incorporated. He got very little money directly from the telegraph.

In Europe, the patents of Wheatstone, Cooke and others prevented him from making any income from his now worldwide telegraph system, although several European countries banded together to give him some small payments in gratitude for his invention. He was also given honors equivalent to Knighthoods by several countries, including Denmark and Turkey. While he was immensely proud of this, it caused him problems back in the United States because accepting such honors should have meant giving up his U. S. citizenship.

Morse also appears to have forgotten those who helped him. He wrote dozens of letters-to-the-editor, depositions, and even books defending himself from charges that Vail, Professor Gale, Dr. Jackson, and numerous others were the true inventors of the Morse telegraph. Rather than graciously offering a bit of credit that was due, he generally claimed all the ideas were his in entirety.

In U. S. court cases, he was largely, but not entirely, successful in defending his patents. Vail, however, received a significant portion of the money Morse made from his inventions. He is also arguably credited with changing Morse code from the ‘word associated with a number’ method used originally to the Morse alphabet code that was eventually adopted for general use. It was also Vail who developed the telegraph key and Gale who created the repeater system that made long-distance transmission possible.

Some of this fighting was unavoidable with such a landmark invention, of course. There were obviously fortunes to be made by those who owned the rights to the telegraph. Some of the fighting appears to have just been Morse’s nature. Long after his patents had run out and his financial success was assured, he continued to write long letters to various newspapers refuting anyone who claimed any shared credit for his invention.

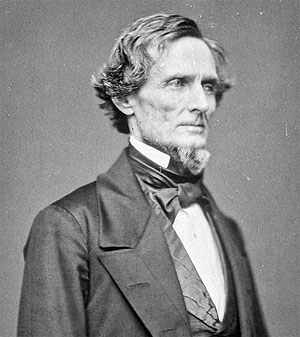

Americans idolized Morse for years after the telegraph was introduced. From his position of fame, he became rather political and wrote at length against--well, basically everything that wasn’t Calvinist American. He ran for office on anti-Catholic, anti-European, and anti-abolitionist platforms (1,2). After being soundly defeated--he received just 759 votes when running for the Mayor of New York--he continued to write numerous political articles.

During the American Civil War he wrote long diatribes attempting to show that the Bible was pro-slavery and organized groups to oppose Lincoln whom he blamed for the Civil War. This might have been better received had he lived in the Confederate States. In his homes of New York and New England, though, it brought public opinion of him to new lows.

Morse returned to Europe for most of the last years of his life, largely because he felt more comfortable there. He finally returned home to New York in 1870. During his last years he was extremely philanthropic, making large donations to churches and educational institutes.

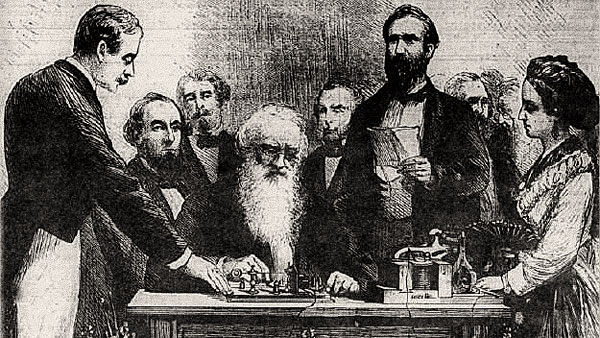

Public opinion of Morse had largely rebounded by that time and on June 10th, 1871 a large celebration of his life took place. It began with the unveiling of a statue of him in Central Park, and ended in a large auditorium where Morse keyed out his last message in Morse code.

Morse died a few months later at age 81. At the time of his death he was writing a last rebuttal to an article written by the curator of the Smithsonian museum that claimed that Vail and Gale, not he, were the true inventors of the telegraph.

(Roger Cicala is the founder of LensRentals.com. Visit LensRentals.com to check out that cool lens you've been hankering for, and for some of the best customer service on the Internet!)

References:

Bellis, Mary (2009). Timeline: Biography of Samuel Morse 1791 – 1872″. The New York Times Company.

http://www.fullbooks.com/Samuel-F-B-Morse-His-Letters-and-Journalsx516.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20061212073521/http://www.morsehistoricsite.org/history/morse.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Morse

http://inventors.about.com/od/mstartinventors/a/samuel_morse.htm

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/Samuel-Morses-Reversal-of-Fortune.html

Mabee, Carleton. The American Leonardo: A Life of Samuel F. Morse. Rev. ed. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2000.

Samuel F. B. Morse Biography – life, parents, death, history, wife, mother, son, information, born, college, time http://www.notablebiographies.com/Mo-Ni/Morse-Samuel-F-B.html#b#ixzz28FHWCgxT

Silverman, Kenneth: Lightning Man: The Accursed Life Of Samuel F.B. Morse. Da Capo Press, 2004.

Images courtesy of Wikipedia and the Library of Congress.