How the American West was won with the help of photographer Timothy O’Sullivan

posted Wednesday, November 14, 2012 at 6:15 PM EDT

Like lots of other kids, I spent Saturdays in our local, somewhat faded movie theater, my eyes glued to the screen as cowboys and Indians wildly rode across a vast, empty landscape. While all of us kids wanted to be cowboys, none of us ever thought about playing one of the Wild West photographers. After all, in the movies and later in TV, such characters were always portrayed as skinny, ineffective men who were always clumsily tripping over their wooden tripods and setting off their flash powder lighting in their own faces. Sadly, like so many of the stereotypes perpetrated by movies and TV about the American West, they got it dead wrong.

The photographers that worked in the West were made of tougher stuff and were arguably more heroic than the cowboys, who were actually latecomers to the party. It's a pity that no one has ever made a movie about them.

One who deserves such treatment is Timothy H. O'Sullivan. O'Sullivan was a sturdy, young man with a large walrus moustache who had worked as a photographer since his teenage years. He got a job at Matthew Brady's portrait studio and, with the onset of the Civil War, became one of the world's first combat photographers. Born in Ireland around 1840, his parents settled in New York two years later. With the outbreak of the Civil War, he enlisted in the Union Army, worked as a surveyor and part-time photographer and, after he was discharged in 1862, rejoined Brady, who sent him out to cover the war.

When you think of a Civil War photo, it may be one of O'Sullivan's. His most famous image, recognizable to most everyone who has read their history, titled, "A Harvest of Death." Made in 1863 after the Battle of Gettysburg, it was staged by O'Sullivan who moved the dead and rearranged their bodies to fit his design. To our modern sensibilities, this may make it a "fake," a manipulated reality, but I think it speaks to O'Sullivan's desire to go beyond simple documentation to create powerful, sensational images.

A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pa., 1863

Photography by Timothy H. O'Sullivan/Library of Congress

In 1867, the War behind him, he used his fame to become the official photographer for the U.S. Geological Service's "Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel." The purpose of the exploration was as much political and promotional as it was scientific. The U.S. was stretching across the continent and the government wanted people to settle the heartland. O'Sullivan's task was to create photographs to sell the West, and induce Easterners and foreign immigrants to settle in the new American territories.

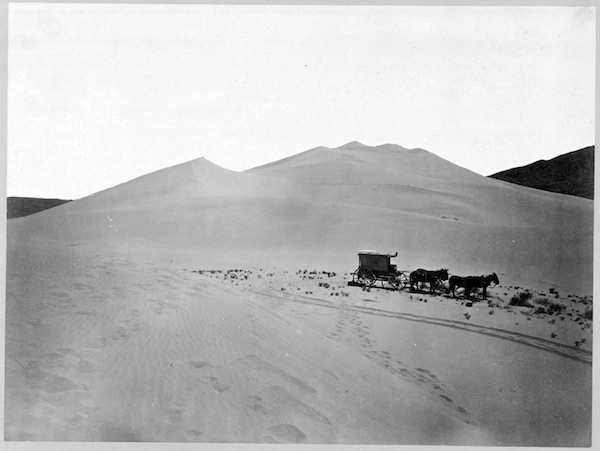

Setting out from Virginia City, Nevada -- a town that would later be immortalized in movies and TV series, including "Bonanza" -- O'Sullivan headed into the Southwest. With boxes of glass plates and a wagon full of chemicals, he made photographs as he traveled using the wet plate collodion process. This process requires the photographer to coat the glass with a syrupy concoction of light-sensitive chemicals and make the exposure while the plate is wet. This means that wherever he went, he brought his darkroom -- an old, horse drawn military ambulance fitted out for photographic processing -- with him. Despite its difficulties, the wet collodion method served O'Sullivan well because it produced the highly detailed, grainless images he was after.

Sand Dunes, Carson Desert, Nevada, 1867 (featuring O'Sullivan's darkroom wagon)

Photograph by Timothy H. O'Sullivan/Library of Congress

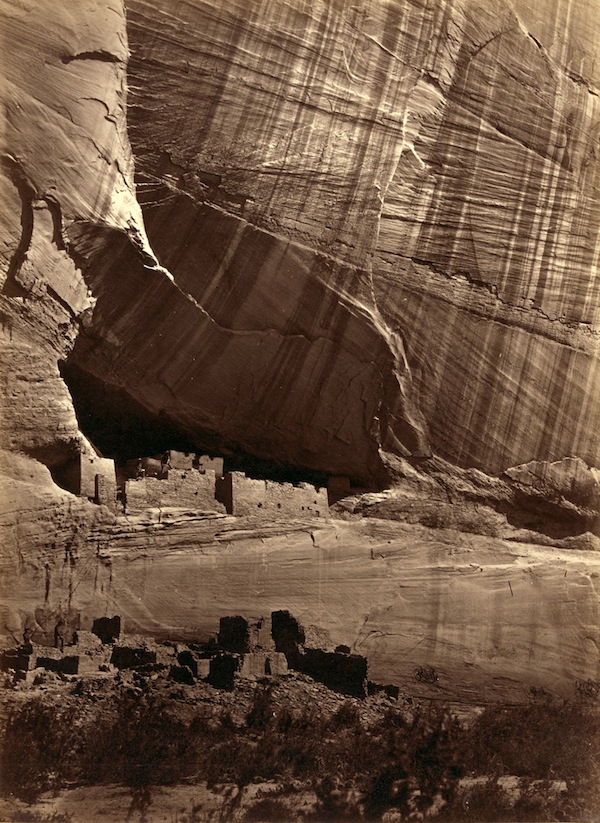

O'Sullivan roamed all over the Southwest, photographing the prehistoric Anasazi ruins of the Canyon de Chelly, pueblo villages and the Navajo peoples of the region. Unlike most other 19th century photographers, however, O'Sullivan's images were much more than scientific records; they captured geological formations and the natural landscape seen through the eyes of an artist.

Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, N.M., 1873

Photograph by Timothy H. O'Sullivan/Library of Congress

When O'Sullivan returned to the East in 1869, his images of the wide-open West mesmerized throngs of urbanites and new immigrants. His pastoral vision of a vast pre-Industrial Eden just the other side of the Mississippi River motivated thousands of city dwellers to leave their cramped, polluted, industrial environs for the new frontier.

O'Sullivan often used a trick in his photos that he learned from the paintings of the Hudson River School of artists. He would place a person -- usually himself -- into his photographs. His small figure, staring at a powerful waterfall, or sitting on a rock promontory overhanging a huge canyon, gave his images a sense of the scale that revealed both the true vastness of the wilderness and the smallness of the humans within it.

Shosone Falls, Idaho, 1868 (with O'Sullivan in foreground)

Photograph by Timothy H. O'Sullivan/Library of Congress

However, O'Sullivan was a restless man, and soon, in 1870, he joined a team surveying the Isthmus of Panama for the canal that was soon to be built there. The next year he returned to the Southwest with another government expedition known as the "100th Meridian West Exploration." This trip turned out to be far more dangerous than anyone had expected. One day, some of the expedition's boats capsized in the rapids of the Colorado River and O'Sullivan and the other explorers nearly starved to death before reaching safety. Unfortunately, most of the 300 negatives he had made on this expedition were lost.

Shaken by this experience, when O'Sullivan returned home to New York, he settled into a job as the official photographer for both the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department. It was a position he held until 1882, when only forty-two-years old, he died of tuberculosis at his home on Staten Island.

O'Sullivan's photographs not only helped to spark the Westward migration that epitomized American Manifest Destiny, but also they served as an inspiration to the next generation of landscape photographers, notably one Ansel Adams.

You can see more of Timothy O'Sullivan's historical photographs of the American West here.

Timothy H. Sullivan, Carson City, Nev. c1871-74

Photograph by F.G. Ludlow