Roman Vishniac: Rediscovering his photographic and enigmatic genius

posted Friday, February 15, 2013 at 8:47 AM EST

The International Center of Photography in New York is presenting an intriguing show of hundreds of photographs by the Russian-American photographer Roman Vishniac from Jan. 18 to May 5, 2013. The title of the exhibition is "Roman Vishniac: Rediscovered," but a better title might have been "The Enigmatic Roman Vishniac."

Photographer and curator Cornell Capa -- younger brother of photojournalist Robert Capa -- introduced me to Vishniac in the late 1960s. He had met Vishniac a couple of years earlier and they had become close friends. Both were secular Jews who had fled Europe to settle in New York City. From that first meeting, it was clear to me that both men were extremely sure of themselves. Their friendship was based on both their common European backgrounds, and their strong belief in photography as a tool for social activism -- a somewhat romantic notion today in the age of the smartphone. Capa and Vishniac felt that if you showed people photographs of social problems, they would take action to fix them. For Capa, Vishniac's photography of the Warsaw Ghetto and village life in Eastern Europe before World War II fit this bill perfectly.

Roman Vishniac, "Nazi Storm Troopers marching next to the Arsenal in front of the Berlin Cathedral", ca. 1935. © Mara Vishniac Kohn.

Courtesy International Center of Photography.

The show at the ICP offers a different view of Vishniac's work that ironically presents a cautionary tale about social activism and the man himself.

'An unchanging, authentic society captured in amber'

The story begins with Vishniac's 1947 book of photos entitled "Polish Jews" that presented a vision of black-bearded yeshiva students, urban poverty and social isolation -- a vision that was spun to life in the hit musical "Fiddler on the Roof." Here was a world of poor but happy Jews who, although facing the end of their bucolic ways of life (if not their lives themselves), could still sing and dance on their rooftops.

But there was something wrong with this image. When I showed my Polish-Jewish grandparents a copy of "Polish Jews," to my surprise they didn't recognize what they saw. It was not their "vanished" world of urbanity, of diverse occupations and vocations, of women in short skirts and men with fast cars, of cabarets and artist cafes, of universities filled with young people and laughter.

Maya Benton is the curator of the Vishniac show at ICP, and she, too, discovered this imbalance in Vishniac's public work. She told the New York Times that the image of Vishniac's photography was, "Rabbi, rabbi, rabbi, followed by -- my favorite -- the sad shopkeepers with nothing to sell, then cheder, cheder, cheder [traditional Jewish elementary school], followed by one alte frau in a babushka."

Roman Vishniac, "Jewish schoolchildren, Mukacevo", ca. 1935–38 © Mara Vishniac Kohn.

Courtesy International Center of Photography.

This, she told the Times, created an unchanging "authentic society captured in amber" rather than a document of what was actually there. Vishniac took these photographs to point out the plight of many poor European Jews, but ended up showing a strange alien world, a world of the "other." It was a world filled with people so different from the ordinary that my Warsaw-born grandparents could not recognize them.

Peeling back the layers of enigma

Benton had long been interested in Vishniac's work and this led her to contact Mara Vishniac Kohn, Roman's daughter, who lived in Santa Barbara, California. Mara had her father's archive of some 16,000 negatives and collections of ephemera stored in a mini-storage facility near her home. Mara was more than 70 years old when Benton met her, and she was worried about the collections' future. Benton suggested that the archive go to ICP out of respect for her father's friendship with Capa. Mara agreed and everything is now at ICP, where it is being cataloged, studied, and the images digitized. This will not be an easy task. Vishniac often cut his favorite frames out of their negative strips, thus losing valuable contextual information about location and date.

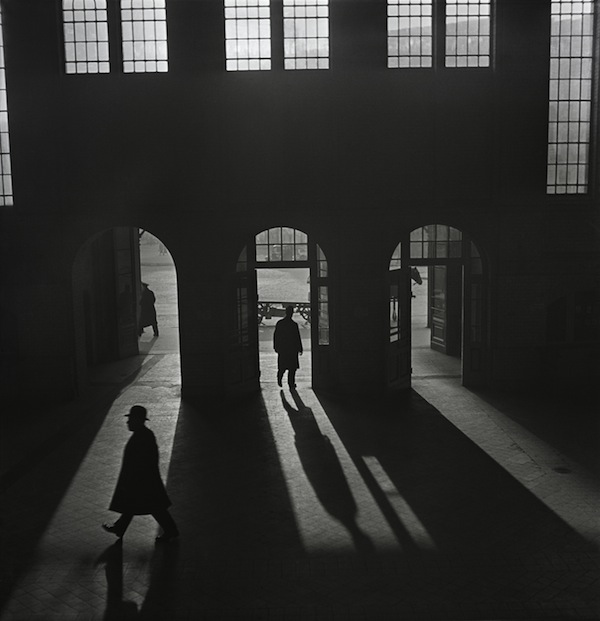

Roman Vishniac, "Interior of the Anhalter Bahnhof railway terminus near Potsdamer Platz, Berlin", late 1920s–early 1930s © Mara Vishniac Kohn.

Courtesy International Center of Photography.

If context was a problem in Vishniac's work, then so was reliability. Michael di Capua, who edited another book of Vishniac's images titled "A Vanished World," was concerned that so many of Visniac's captions were unsubstantiated or vague. To get around his concern, di Capua put all the captions on the first pages preceding the photographs to lessen their impact.

As Benton went through Vishniac's archives she made another discovery. She told the Times: "Not only do the unpublished photographs offer a kaleidoscopic view of prewar Jewish life -- women in modern dress and men without hats, religious people comfortably consorting with secular people, shopkeepers with plenty of wares -- they also convey a fuller sense of the photographer's artistic abilities."

Part of the ICP's "Roman Vishniac: Rediscovered" exhibit is Benton's attempt to show that Vishniac was a better photographer than people thought. In the past, Vishniac's photos had been criticized as mundane and unimaginative. This is perhaps the heart of the rediscovery of Vishniac.

A child armed with a microscope and a camera

When Capa introduced me to Vishniac, he did so by saying we both had an interest in nature. He said that I was working on a research project in college with Amazonian electric eels. This got Vishniac's attention, as nature was a central theme of his life.

Born in 1897, Vishniac was an accomplished biologist who made significant scientific contributions to photomicroscopy and time-lapse photography. He came from a wealthy family -- his father was the leading parasol maker in Russia -- and the story goes that as a child he was given a microscope and a camera. He immediately put the two together and began his life's work of exploring the invisible universe of the very small. After leaving University, he became a pioneer in time-lapse photography and, between 1914 and 1918, developed some of the fundamental techniques we still use today.

Vishniac was a first class cine-microscopist, creating hundreds of scientific films and through them, a whole generation of students learned biology. He became a professor of biology and art education in the 1950s. Throughout his career his color photographs appeared in hundreds of magazines, and on the covers of Life, OMNI, Nature, and Science magazines. The ICP show has a few -- far too few -- of Visniac's nature photos. He died in 1990, and I hope as his archive is explored more of his work will be exhibited, especially these that show a much different vision.

Roman Vishniac, "Cross section of a pine needle", date unknown. © Mara Vishniac Kohn.

Courtesy International Center of Photography.

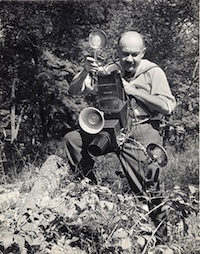

The scientist and photographer often spent weekends hiking around New York City and its outskirts toting his large, homemade photo microscopy rig, shown in the photo at the top of this article. He loved photographing nature in the suburban wilds. Vishniac showed me some of these images, both his color and black and white shots. They were wonderful moments of insects caught in mid-flight or in mid-sex that had an elegance that was surprising in nature photography.

By the way, Vishniac had an important tip for nature photographers like myself. Before taking any pictures, spend some time rolling around in the grass and foliage near your shooting location. This will cover your body with natural smells and make your presence less disturbing to your subjects, especially those in the throes of passion.

If you can't get to New York for the "Roman Vishniac: Rediscovered" exhibit, you can see it online at the ICP website. (Of course, it's always better to see such shows in person, but unfortunately we can't travel to see them all!)

Roman Vishniac, "People behind bars, Berlin Zoo", early 1930s. © Mara Vishniac Kohn.

Courtesy International Center of Photography.