A Lion in Winter: The revolutionary street and commercial photography of William Klein

posted Thursday, May 30, 2013 at 5:43 PM EST

The French photography magazine PHOTO recently devoted its entire May issue to 85-year-old American photographer and iconoclast William Klein. Born in New York City in 1928, Klein has mostly lived in Paris since 1948, which has done little to endear him in America. His photography was labeled outright un-American in the 1950s, and his 1969 movie titled "Mr. Freedom" did little to change that impression. The film is an almost unwatchable spoof of American culture that film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum called “conceivably the most anti-American movie ever made.” As an artist and social critic, Klein was a firebrand, a revolutionary, a lion -- with the wild mane to go with it.

In-your-face photographer

Klein first got noticed through his street photography. Compared to the sweet images of Garry Winogrand, Klein’s world is an in-your-face kaleidoscopic place, where faces are often grotesque and disturbing. He crosses the boundaries of politeness and charm, and takes us by the scruff of the neck into the world of his subjects.

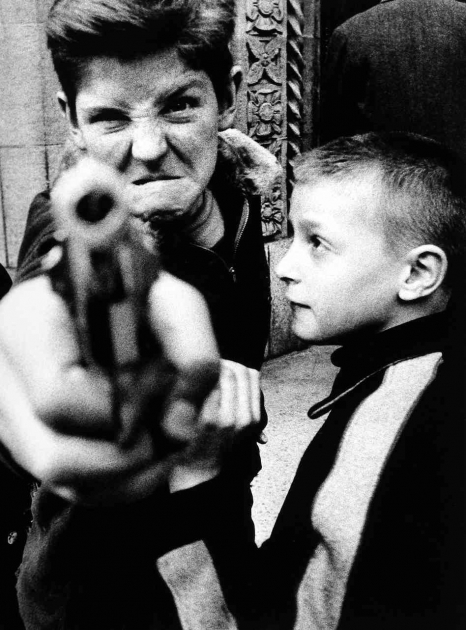

On the streets of New York in the mid-1950s, he discovered blur and learned to use it to draw the viewer into the heart of the image. Take his most famous image “The Gun.” It sums up his discovery of blur. The business end of the gun is completely out-of-focus, but it pulls us right into the eyes of the kid holding the gun and his scrunched up face. It is the face you make just as you are about to pull the trigger.

The gun is aimed at the viewer. That in itself is remarkable. How many pictures can you think of that confront the viewer so directly? The image asks “What are you looking at?” It mirrors the world that Klein grew up in, and it is, as he says, very much a self-portrait. The image affects me deeply because I grew up in New York City where the streets were tough and violence was never far away. I knew kids like this -- in fact, I was one of them. And like many of my friends, I graduated from a toy Lone Ranger cap gun to a zip gun and then to a .38.

Gun 1, New York, 1955 © William Klein

A self-taught outsider

The son of Hungarian immigrants, Klein grew up in New York City and attended City College for a short while. In 1946, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, spending his tour of duty in postwar Germany. Demobilized in 1948, he moved to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne where he studied art with Fernand Léger. He was interested in abstract painting and sculpture, and by 1952 had held several successful solo exhibitions. Then he found himself attracted to photography, which he saw as a field wide open with possibilities. Returning to New York in 1954, he decided to photograph the city and his old familiar haunts. As he tells it:

“I’m an outsider, I guess, I wasn’t part of any movement. I was working alone, following my instinct. I had no real respect for good technique because I didn’t know what it was. I was self-taught, so that stuff didn’t matter to me.”

His disrespect for good technique led to some groundbreaking imagery as he just stuck his camera in people’s faces and took pictures -- sometimes so close the faces were out of focus. Klein realized that foreground blur could pull the viewers eyes deep into the frame, and since he didn’t know better, it was revolutionary.

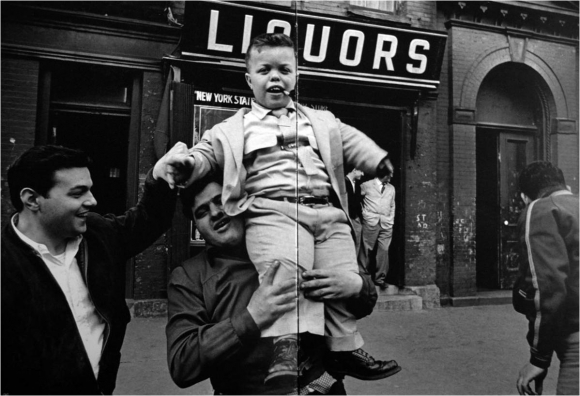

Grace Line, New York, © William Klein

After a year of shooting in New York City, Klein put together a book of his photographs and tried peddling it to various New York publishers. At the time, the “Mad Men” ruled the publishing industry. Showing his photos to one publishing executive, he was told they were un-American because they made New York City look like a slum. Klein told the exec that he obviously knew nothing about the real New York City since he lived on 5th Avenue and worked on Madison Avenue. “Have you ever been to the Bronx?” Klein asked.

Apparently none of the publishers had been to the Bronx because no one wanted his book.

Vitelloni, 29th Street and Second Avenue, 1954-55 © William Klein

A triumphant return to Europe

Klein returned to Paris and tried again, and this time he found a publisher, Chris Marker of Seuil Editions. His book of photography titled "New York" was published in 1956 and won the Prix Nadar. A copy of it was also purchased by Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini.

When Fellini was on a visit to Paris, he met the young photographer and invited him to work on his next film, "Nights of Cabiria." Klein knew nothing about movie making, but was always ready to grab at an opportunity. He packed up his cameras and his wife Jeanne, and went off to Rome. Fellini was notorious for his production delays, and "Nights of Cabiria" went into a stall. With no work, Klein used his time to wander around Rome and do what he did best -- take street photographs. The resulting images were published in late 1957 as his next book titled “Rome.”

Simone, Piazza di Spagna, 1960 © William Klein

Klein got into commercial work after Alexander Liberman, the legendary art director of Vogue, saw an exhibition of his abstract photographs and offered him a job. Says Klein:

"Those guys spotted raw talent and encouraged it. They were all Russian Jews in exile: Liberman at Vogue, Alexey Brodovitch at Harper's Bazaar. They had a knowledge of avant garde art and design that the Americans didn't have."

In 1958, Klein's photographs first appeared in Vogue, and for the next 10 years he worked for the magazine. In the book "Photography of the 20th Century," Klein's fashion work is described as revolutionary for its "ambivalent and ironic approach to the world of fashion" and its "uncompromising rejection of the then prevailing rules of photography." Some of those "rules" today may seem bizarre and laughable as Klein's revolution included shooting with wide-angle and telephoto lenses, using natural lighting and -- OMG -- blur.

Hat and Five Roses, Paris (Vogue), 1956, cover of book In & Out of Fashion, Paris, 1994 © William Klein

He also continued taking street photographs when he could, also finishing a book on "Moscow" and another on "Tokyo" before finally finding an American publisher for "New York." However, by 1964 he was bored and restless -- so he started making films.

Bikini, Moscow, 1959 © William Klein

Films and commercial pursuits

Working with Fellini, Klein had fallen in love with movie making and after leaving Vogue he began producing and directing films. His first feature was "Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?" in 1966, and in 1969 he made his most successful film, "Muhammad Ali, The Greatest." His third film was the “Little Richard Story” but the musician is hardly present in the film. (Critics jokingly called it “The Search for Little Richard.”) His 1981 documentary, "The French" about tennis star Roland Garros also was well received. But there were the disasters too, such as “Mr. Freedom.” It was a film mostly notable for the appearance of famed French singer-songwriter Serge Gainsbourg in the role of Monsieur Drugstore.

Despite his early run ins with the publishing world and the "Mad Men" of the 1950s, Klein eventually went on to have a long career in advertising. He has produced more than 250 TV commercials and shot untold numbers of advertising stills.

In his old age, the lion time and again has been lionized. There have been several retrospectives made of his work, and the awards have poured in. He has received the Royal Photographic Society's Centenary Medal, Sony’s Contribution to Photography Award (in 2012) and many more. Professional Photographer Magazine ranked Klein No. 25 on its "100 Most Influential Photographers of the Century" list.

Older and more tranquil, the lion continues to work. At age 83, he went off to England in 2011 for the royal wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton. Rather than spend time with the society folks, though, Klein spent his time prowling through the crowded streets of London. As usual he would take photographs poking his camera into people’s faces. Although street photography has gotten more difficult as people respond more angrily to photographers, Klein was perhaps protected them by his age and his great grey mane of hair.

In this video produced by the Tate Gallery of London, it appears that Klein may have mellowed a bit, but he still speaks his mind. From his den, the old lion reminisces about his life and images -- his long mane of grey hair framed by a faded red hoodie as he speaks softly in a voice that retains its New York accent and attitude.