Astronomical beauty: How one photographer pulls heaven down to earth for the rest of us to see

posted Wednesday, August 6, 2014 at 8:26 AM EDT

I've loved both astronomy and photography since I was a kid, so seeing awesome photographs of objects from the heavens has always fascinated me. As such, it's been only natural that the first thing I've done for the past ten years over coffee every morning is to check out NASA's Astronomy Photo of the Day page to see what's new out there in the cosmos.

Every now and then I come across an especially interesting or inspiring entry, and this recent one on June 29, 2014 called Galaxy Cove Vista Revisited by Rogelio Bernal Andreo certainly fits that description.

I was so intrigued with this image that I contacted Rogelio to see if he'd share more about his work and techniques with our readers, and he graciously agreed. Below is a brief interview with him regarding his work in astrophotography over the past seven years. I hope you all find it as interesting as I did! Please feel free to share your comments, compliments and questions about Rogelio's work in the comments section below this article.

Imaging Resource interview with Rogelio Bernal Andreo

IR: When did you decide to start shooting deep sky imagery and what was your initial inspiration?

RBA: On September 2007 I was driving the Pacific Coast Highway south of Big Sur in California with the family, when my wife opened the moonroof of the car, looked up and screamed "You have to pull over, you have to see this!" referring to the starry sky that was above us, me unaware, due to being "blinded" by the car lights. I pulled over, and there I was, well into my 30's, staring at the Milky Way for the first time in my life. I had my camera and tripod so I tried to capture that mesmerizing view, but it was a complete disaster. I didn't mind, and we spent a couple of hours at that turnout watching a night sky as I had never seen before. I'd gotten intrigued about how people take pictures of galaxies and nebulas, so the next day I went onto the Internet, and hundreds... thousands of hours spent on this discipline did the rest.

IR: In the Wikipedia page describing your professional background, it discusses your early use of post-processing techniques not common at the time you began exploring them. Can you give our readers some background on your technique, and how it's evolved over time?

RBA: The Wikipedia article refers to multi-scale techniques, which in short, generally means breaking the image into different scales, apply processes to large and small scale structures separately, and then recombine them. I am not the first person using these techniques, and in fact, some commercial applications use multi-scale techniques internally, but it's possible that I might have helped making these techniques popular in the astroimaging community.

[NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day • December 29, 2009 and November 1st, 2012]

IR: Which technological advances have been the most beneficial to your type work, both in the field and in post-processing?

RBA: In my case, the only advances have been happening in the field of data post-processing. I use a CCD camera that was first manufactured more than ten years ago, and the telescope and mount models aren't any younger. However, when I first got into astrophotography, almost everybody was using Photoshop to process their images, and while Photoshop is the very best photo editing software on the planet, it is not well suited by many of the problems that we find in astroimages, such as linear data editing for example. I quickly discovered this software called PixInsight being developed in Spain, which is an image processing platform specifically developed for editing astroimages. From that day I downloaded the software back in 2007 until now, they have hugely improved the software, adding tons of tools that have helped me greatly in my images, and they continue to do so. It is PixInsight the software that included the multi-scale processes I mentioned earlier, for example.

Leaving post-processing aside, we should expect better sensors. We don't need smaller pixels but sensors that are more sensitive and less noisy. Better signal-to-noise means better data in less time. There's a lot going on in the CMOS area, while not much in the CCD world. If this trend continues, I expect we soon will see astro cameras with CMOS sensors.

[Click here to see more about Rogelio's full astrophotography gear arsenal]

IR: Are you currently working on any special projects you'd like to share with our readers?

RBA: Absolutely. I am 100% immersed in the final steps of publishing my first book. It's not about deep sky images, but nightscapes. It's called Hawai'i Nights, and it really is a never seen before tour of the Hawaiian night sky. I define it as a live photographic experience that brings to you images of Milky Way arches above enchanting beaches, glowing volcanoes, lunar rainbows, sea cliffs, mysterious abandoned resorts at night, palm tree forests under thousands of stars, and many more surprising and captivating nightscapes - 70 images at the moment - all in a "first of its kind" collection that is sure to transport you to a heavenly side of Hawaiʻi not many people have ever experienced.

Plug aside, to me this really was a project that had to be made sooner or later, because the landscape and night skies of Hawai'i deserve it, and I think my particular initiative is, at the very least, a fair first attempt.

IR: (We agree!)

RBA: Another project I've been working on for a while is a series of tutorials in astroimage post-processing, where another astroimager (Warren Keller) and I are really covering virtually everything there is to deep-sky image processing, including of course, multi-scale techniques. It's a commercial product, but there's some free complete "samples" available here.

IR: Do you have one image that was a bigger breakthrough in terms of what you were able to achieve in capturing it?

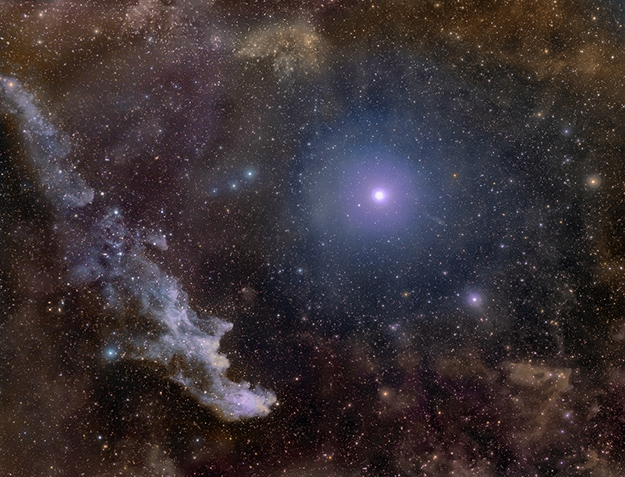

RBA: I can think of many images, but there's one that really made a difference in the way I looked at deep-sky astroimaging. That's the Angel Nebula:

This nebula is made out of interstellar dust reflecting the light of our own galaxy, unlike most nebulae which shine either because they emit light or reflect the light from nearby stars. It is therefore extremely faint and if often does not appear in astroimages which show instead a starry but flat and dark background. It's not the most beautiful or challenging image I've produced. However, it awoke my interest for very faint nebulosity and dust, something that became a trend for me the following years, even today. I love trying to unveil a part of our universe that is rarely depicted in images.

IR: Are there current roadblocks to your work that you hope technology will someday be able to help you overcome?

RBA: I think we're actually in pretty good shape. Astroimaging is all about collecting faint light and dealing with data that contains both, signal and noise. Increasing the aperture of our telescopes is a matter of space and costs, not technology, so the only areas where technology can help us take better, deeper images of the deep sky are tracking and sensor technology. It is already possible to take hours of a single exposure with the current tracking technology, but even better tracking (telescope moving at sidereal speed, "following" the sky) would make our job easier. Now, more sensitive and less noisy sensors are helping going deeper than ever before, and here I think we'll be seeing tremendous advances in years to come. I joke about one day we'd be taking our cell phone, point it at the sky, take a photo, click, and voila, here's the Orion Nebula!

IR: Is there any general advice you can give to photographers aspiring to capture the types of deep sky subject matter that you like to shoot? (this can be about gear, technique, locations, etc):

RBA: I think this discipline is complex enough to require different advice depending on where you are in the learning curve. I'd tell someone who's just starting to spend as much as they can in the mount, not the telescope or the camera. To someone who's somewhat seasoned but too focused on producing images "like XYZ astrophotographer", I might advise them to stop looking at what others do and work more on what their own vision is.

If anything, do not be discouraged by the hard fact that, while the operator is always important, money does buy quality. Aim at doing better each time with the equipment you have, and just upgrade your gear - be it the scope, mount, camera, etc. - whenever you can afford it comfortably (do not break the bank). If you're at the top in what you can afford and feel you've reached the ceiling on what you can accomplish with that gear, just keep exploring the sky, maybe swap your scope for one of a different focal length, which will define a different list of the things you can do.

IR: We'd like to say an enormous Thank You to Rogelio for sharing his time, insights into astrophotography and incredible images with us. And thanks to the heavens that his wife opened their moonroof in Big Sur in 2007 - the world is a richer place for images like his.

To see many more, head over to his website DeepSkyColors.com.

[All images copyright © Rogelio Bernal Andreo / DeepSkyColors.com]

[NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day • June 29, 2014]