Ceramic portraits that survive the ages: A quick glimpse at an old-school printing technique

posted Thursday, March 19, 2015 at 12:20 PM EST

My mom's mom's dad, Emil Koellein, was a professional photographer in Nashville, Tennessee after the Civil War. He and his partners ran a successful photography studio, and a quick internet search turns up lots of examples of their work.

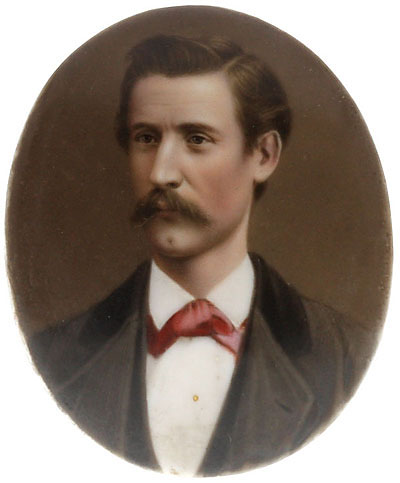

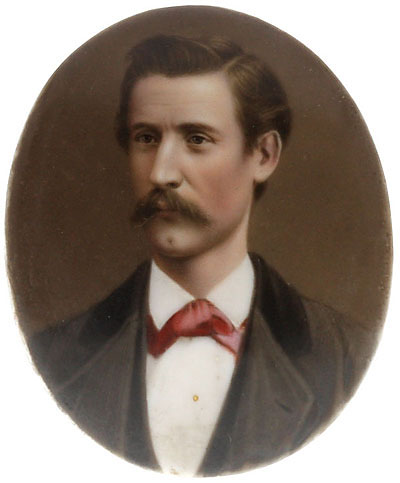

I have several nice portraits of Emil and his wife, Mathilda. Apparently, Emil and his partners took photos of each other when business was slow. These are big, lovely, sepia prints, with super-sharp details, and smooth blur where appropriate, all thoroughly professional. He was a pretty sharp dude, in a long-faced German way.

I have one other smaller portrait of Emil, though, that has always intrigued me. It's on a little oval convex ceramic plate, just a couple inches wide, and it is in (hand-tinted) color.

(Check out that dimple!)

This little ceramic photo has held up very well over the last 135 years, or so. I'm sure it has been handled by dozens of my forebears and relatives in that time, but it still looks pretty much new. So, how was it made? How does one make a permanent photographic image fired into ceramic?

A little online detective work provided some possible answers. These small ceramic portraits became common in the USA in the late 1800's as photography became more popular, but had originated earlier in Europe. A couple of Frenchmen, Bulot and Cattin, developed the process and received patents on it back in 1854. The photos were particularly popular in Italy, but also with various ethnic groups and religions in other parts of Europe. They were frequently used on gravestones as an affordable permanent likeness of the deceased, instead of hiring a sculptor to carve an image in stone. European immigrants brought the custom with them, and examples can be found in the cemeteries of areas where they settled in America.

from her website HeadstonesandHistory.com

[Photos used with permission | © Laurel Mellien]

Photography in Emil's day involved a light-sensitive collodian or gelatin coating on a glass plate, and produced a silver negative image. Making a copy of that negative would produce a positive image. This image could be transferred by soaking it, and physically sliding the collodian layer from the glass plate to the final ceramic plate. The metallic silver image remained intact when the ceramic was fired in a kiln. Tinting could be done with ceramic pigments, which would also hold up during firing.

Ceramic prints are still being made today, with modern techniques and materials, Photoshop, inkjet printers, and, of course, handy online ordering. Some craftsmen in Italy still do it the traditional way, using hand-transferred photographs.

I don't know whether my great-grandad created this as a sales tool or as a family keepsake, but either way it's still a nice window into my past. (That's my nose, alright.)

• • •

[Luke Smith is the senior lab technician for The Imaging Resource and has shot the majority of our test images for more than ten years. He's a big reason for the ongoing success and testing continuity of our website.]