The perfect lens doesn’t exist and getting close to perfect is expensive

posted Monday, February 8, 2016 at 1:15 PM EDT

Many of us only have the opportunity to use one copy of any particular lens. It isn't practical for the end-user to test different versions of the same lens before settling on one, nor is it good for retailers if consumers are cycling through lenses. Supposing that you had the equipment to accurately test your lenses (which you probably don't), your own lens will never be as good as the theoretical MTF that the manufacturer publishes.

As LensRentals founder and co-owner Roger Cicala says in his post on LensRentals, "Perfect doesn't exist. For $20,000 and up you can get pretty close. For $2,000 you should be able to get reasonably close."

When getting reasonably close to perfect with your expensive lens, you should expect that your copy of the lens won't be different from someone else's copy of that same lens in any critical way. According to Cicala, some manufacturers deliver good quality control, while others come up short. What can be done about this?

No matter how you slice it, higher quality lenses use higher quality materials, and these higher quality materials simply cost more than lower quality materials, no matter how many bulk discounts or economies of scale might exist. Further, testing lenses is expensive, especially if you want accuracy. Per Cicala, "a state-of-the-art MTF bench costs between $250,000 and $500,000." In addition to that, manufacturers need to dedicate time to actually test the lens, which is a cost as well. Roger thinks that an efficient company could test prime lenses for $20 per unit and zoom lenses for $60, assuming economies of scale.

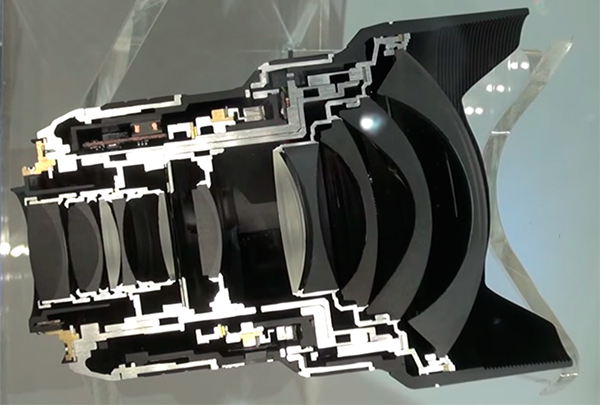

(Image courtesy of LensRentals.)

This might not seem like a lot of cost, but consider what happens when a lens fails optical testing. A more consumer-oriented lens might just be thrown in the trash, according to Cicala, as it's not worth the time to disassemble, reassemble, and retest the lens. More expensive, professional-grade lenses might be disassembled and reassembled. In either case, this is adding cost. At some point, a manufacturer might see a large number of lenses failing and think that it's time to lower the standard, rather than continue to increase their cost (which must be passed on to the consumer).

(For additional insight into lens design, see the two videos below from Nikon Asia, which feature the design team behind Nikon's newest 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR discussing their process.)

So far we have only considered what happens when the lens is being manufactured, but a lot of cost and optical quality assurance takes place well before the lens makes it to assembly. The process of designing a lens is immediately constrained by various concerns for the final product, such as what its price should be, what sort of features it needs to include, how big it should be, and when it should be ready to release. Considering how many elements are often found in modern lenses, many of them featuring different shapes and sizes with different types of materials and coatings, each of them needs to be made within a certain tolerance. There will always be variation, and manufacturers need to determine how much variation there is in each of the elements that they're going to use and how different levels of variation affects the overall performance of the lens. For much more discussion on optical, mechanical, and assembly design, see the full LensRentals article here.

How do things go wrong? Supposing that a manufacturer has made it through the design process, they should end up manufacturing lenses that are quite consistent, right? Well…maybe. Not every manufacturer performs optical, mechanical, and assembly design in-house, nor do they all use in-house parts and production processes. Sometimes there is a disconnect between the team that designs a lens, the team that builds the parts, and the team that makes sure that the parts all work together nicely. The design process is reliant on the actual parts consistently meeting a certain quality, but this doesn't always happen. Even a slight variation in quality can have drastic impacts on lens-to-lens consistency.

Recall how expensive, with regard to both materials and time, it is to adequately test lenses. In reality, not every lens that is made is tested, and the ones that are tested are not necessarily tested to the extent that is necessary to determine optical variation. This is just one of the compromises that must be made with the quality of a lens. There are financial considerations that must be made, certain price points, manufacturing costs, and performance levels that must be met. You have a wide variety of people with different agendas for each lens that a company makes that all have to come to some sort of common understanding. After performing numerous theoretical tests using theoretical levels of variation for all the different components in a lens, a manufacturer may be confident that they'll be shipping consistent lenses. They've invested a lot of money into their lenses and they need to make a return on their investment. If a lens is failing quality assurance testing, the next step might not be to go back to the drawing board, but rather to lower the bar.

While that may be a frustrating prospect, companies understand that better quality assurance and optical testing benefit them in the long run. Consumers rarely forget a bad experience with a particular company, and they are often not silent about it with their friends and colleagues. In the end, the LensRentals team are hopeful that manufacturers will continue to improve their quality control and work to reduce sample variation with their lenses.

For much more information, read the full article here. It's an excellent read that gives a lot of expert insight on how lenses are designed and manufactured and just how expensive it is to make not just one great lens, but to ensure that all copies of that lens are great.

Seen via The Digital Picture.

(Creative commons index image by Flickr user Karl-Ludwig Poggemann, cropped.)