Determination, debt and lonely death: The brilliant rise and tragic fall of Carleton Watkins

posted Monday, May 9, 2016 at 11:12 AM EST

Last week, Bokeh discussed a video from Getty Images about late photographer Carleton E. Watkins. While the video (seen below) is a year old and nothing new has arisen regarding Watkins, this does provide a good opportunity to discuss Watkins and his important contributions both to photography and to America's National Park System.

Early life and affinity for photography

Carleton E. Watkins was born in New York in 1829. Inspired by the gold rush, he moved to California in 1851 but became drawn to photography after a few years in San Francisco. His introduction to photography actually came through a stint as a store clerk down the street from Daguerreotype photographer Robert Vance's studio. When there was an unexpected opening at Vance's studio, Watkins was hired to look after the studio.

Vance taught Watkins the basics of photography so that in his absence, Watkins could take portraits, although Vance intended to have to retake them himself upon his return. This isn't what happened, however, as Watkins' natural affinity for the medium produced satisfactory portraits despite his minimal training.

In 1858, Watkins started his own photography business. A distinct offering of his were three-dimensional photos, Daguerreotype stereoviews which when viewed through a stereoscope gave the viewer a sense of depth.

The rise: Yosemite

With a mammoth-plate camera, which used 18 x 22-inch glass plates, Carleton travelled to Yosemite during the summer of 1861. He also took his stereoscopic camera, but for images with great depth, he used his mammoth camera. Returning from his trip with 30 plates and 100 stereoview negatives, Carleton had started down a path that would not only change the trajectory of his career and life, but also change how natural areas were preserved in the United States.

While it may be hard to imagine now, there was a time when people along the east coast of the United States, and even out west, had no idea what sort of natural beauty Yosemite contained. You couldn't simply view images of this place, as it was generally unexplored and uncaptured. High-ranking politicians were so impressed with the images that Watkins captured of Yosemite that they ensured that it would become a protected natural resource. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln signed a bill, The Yosemite Grant, protecting the land from commercial use. This bill, signed during the tumultuous American Civil War, is considered by many to be the first step toward environmentalism in the American political system.

As you can see in the video above from Zocalo Public Square, panelists discuss not only Watkins' work, but also the context in which his work should be viewed. His camera required a horse and cart, and for him to traverse areas that are difficult to imagine hiking through with just a mirrorless camera in a backpack, let alone a massive camera, gigantic pieces of glass and the chemicals needed to expose them. It is easy to see how Watkins can be described as having been "the hardest working photographer in California."

The first fall, rebound and second fall

Despite having been awarded much critical acclaim and numerous awards, Watkins was hit hard by the financial crisis in 1875. He lost everything: His studio, his negatives, it was all gone. Not only were his negatives lost to a creditor, but the creditor started selling the negatives along with a photographer, Isaiah West Taber, under Taber's name. There wasn't a legal framework for Watkins to seek damages or restitution at that time.

Undeterred, he returned to Yosemite to begin recapturing the images he had lost. He continued to travel and photograph along the western part of North America, from British Columbia down to Mexico.

However, he experienced additional setbacks in the 1890s as his eyesight and physical health deteriorated.

In 1895, the once successful and very influential photographer who had been described by a New York Times art critic in 1862 as having produced "unequaled" works of art was unable to pay rent, and was forced to live his with his family in an abandoned railroad car for 18 months. By 1897, the man who had changed how Americans viewed the great outdoors with his visionary approach to photography was blind.

No phoenix rises from the ashes

Life continued to worsen for Watkins when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and resulting fire destroyed many negatives and almost all of his stereoviews. Unfortunately, this devastated Watkins and he was committed to a hospital for the insane a few years later. Six years after being admitted into the asylum, Carleton Watkins died at the age of 87 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

While it is far too late for Watkins to be celebrated in the way that he deserved, it is not too late to look back and recognize the important contributions he made not only to photography as an art form, but also to Yosemite National Park and the National Parks System in general. It is impossible to truly appreciate all that was lost when his negatives were essentially stolen from him and later when his newer negatives were destroyed by fire, but it is nonetheless important to enjoy what remains of Carleton Watkins' work. To view high-resolution photos of Watkins' work, see here and here.

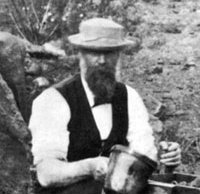

(Seen via Bokeh and DIY Photography with addtional information from Wikipedia, The National Gallery of Art, and Smithsonian. Index image: Self-portrait, 1883)